Setting up a simulation in LAMMPS

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

What are molecular dynamics simulations?

How do we setup a simulation in LAMMPS?

Objectives

Understand the commands, keywords, and parameters necessary to setup a LAMMPS MD simulation.

What is Molecular Dynamics

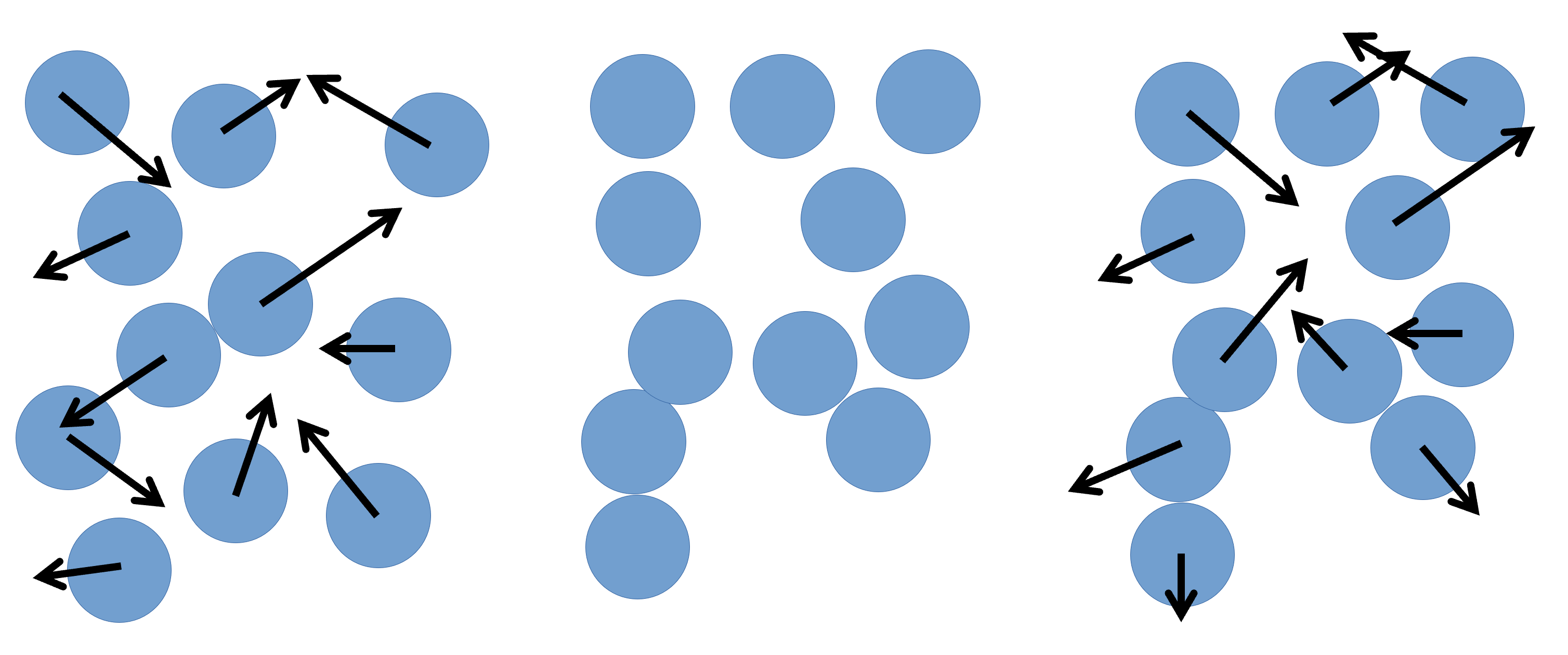

Molecular Dynamics is the application of Newton’s laws of motion to systems of particles that can range in size from atoms, course-grained moieties, entire molecules, or even grains of sand. In practical terms, any MD software follows the same basic steps:

- Take the initial positions of the particles in the simulation box and calculate the total force that apply to each particle, using the chosen force-field.

- Use the calculated forces to calculate the acceleration to add to each particle.

- Use the acceleration to calculate the new velocity of each particle.

- Use the the new velocity of each particle, and the defined time-step, to calculate a new position for each particle.

- Repeat ad nauseum.

With the new particle positions, the cycle continues, one very small time-step at a time.

With this in mind, we can take a look at a very simple example of a LAMMPS input file,

in.lj_exercise, and discuss each command – and their related concepts – one by one.

The order that the commands appear in can be important, depending on the exact details.

Always refer to the LAMMPS manual to check.

For this session, we’ll be looking at the 2-lj-exercise/in.lj_exercise file in your exercises directory.

Simulation setup

The first thing we have to do is chose a style of units.

This can be achieved by the units command:

units lj

LAMMPS has several different unit styles,

useful in different types of simulations.

In this example, we are using lj, or Lennard-Jones (LJ) units.

These are dimensionless units, that are defined on the LJ potential parameters.

They are computationally advantageous because they’re usually close to unity,

and required less precise (lower number of bits) floating point variables –

which in turn reduced the memory requirements, and increased calculation speed.

The next line defines what style of atoms (LAMMPS’s terminology for particle) to use:

atom_style atomic

The atom style impacts on what

attributes each atom has associated with it – this cannot be changed during a simulation.

Every style stores: coordinates, velocities, atom IDs, and atom types.

The atomic style doesn’t add any further attributes, but other styles will store additional information.

We then define the number of dimensions in our system:

dimension 3

LAMMPS is also capable of simulating two-dimensional systems.

The boundary command sets the styles for the boundaries for the simulation box.

boundary p p p

Each of the three letters after the keyword corresponds to a direction (x, y, z), and p means that the selected boundary is to be periodic.

Other boundary conditions are available (fixed, shrink-wrapped, and shrink-wrapped with minimum).

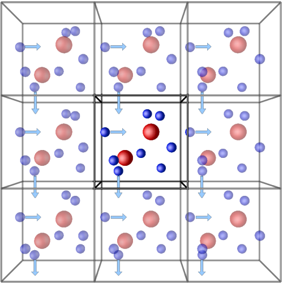

Periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) allow the approximation of an infinite system by simulating only a small part, a unit-cell. The most common shapes of (3D) unit-cell is cuboidal, but any shape that completely tessellates 3D space can be used. The topology of PBCs is such that a particle leaving one side of the unit cell, it reappears on the other side. A 2D map with PBC could be perfectly mapped to a torus.

Another key aspect of using PBCs is the use of the minimum-image convention for calculating interactions between particles. This guarantees that each particle interacts only with the closest image of another particle, no matter with unit-cell (the original simulation box or one of the periodic images) it belongs to.

The lattice command defines a set of points in space, where sc is simple cubic.

lattice sc ${DENSITY}

We have defined our density earlier using the variable DENSITY equal 0.8 command.

In this case, because we are working in LJ units, the number 0.80 refers to the reduced LJ density ρ*.

The region command defines a geometric region in space.

region box block 0 10 0 10 0 10

The arguments are box, a name we give to the region, block, the type of region (cuboid),

and the numbers are the min and max values for x, y, and z.

We then create a box with one atom type, using the region we defined previously

create_box 1 region1

And finally, we create the atoms in the box, using the box and lattice previously created

create_atoms 1 box

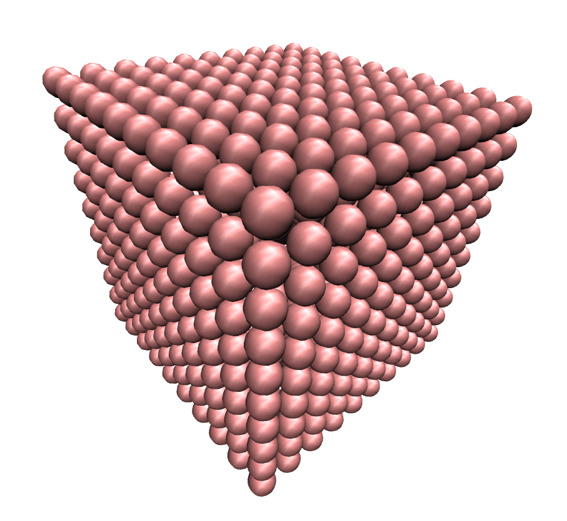

The final result is a box like this:

Inter-particle interactions

Now that we have initial positions for our particles in a simulation box, we have to define how they will interact with each-other.

The first line in this section defines the style of interaction our particles will use.

pair_style lj/cut 3.5

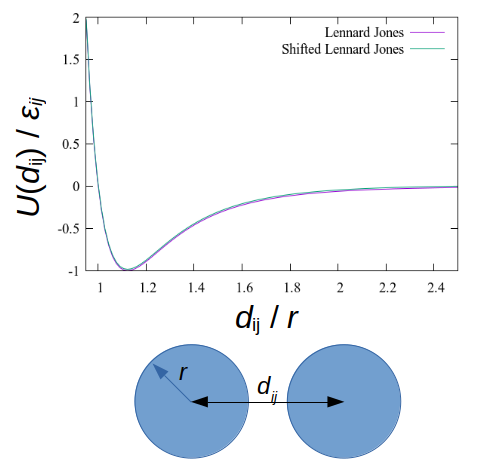

LAMMPS has a large number of pairwise interparticle interactions available. In this case, we are using Lennard-Jones interactions, cut at 3.5 Å. Cutting the interactions at a certain distance (as opposed to calculating interactions up to an ‘infinite’ distance, drastically reduces the computation time required to calculate the energy on each particle. This approximation works because the LJ potential is asymptotic to zero at high interparticle distances d.

To make sure there is no discontinuity at the cutoff point, we can shift the potential. This subtracts the value of the potential at the cutoff point (which should be very low) from the entire function, making the energy at the cutoff equal to zero.

pair_modify shift yes

Next we set the LJ parameters for the interactions between atom.

In this example, we only have one type of atoms, and so only need to worry about interactions between atoms of type 1 with other atoms of type 1

(usually, there are more types – e.g. look at the in.ethanol file from exercise 1).

We define the minimum energy between two particles (ε) and the particle diameter (σ).

Note that these are both relative to the non-shifted potential.

pair_coeff 1 1 1.0 1.0

Finally, we set the mass of atom type 1 to 1.0 units:

mass 1 1.0

There are many other characteristics that may be needed for a given simulation. For example, LAMMPS has functions to simulate bonds, angles, dihedrals, improper angles, and more.

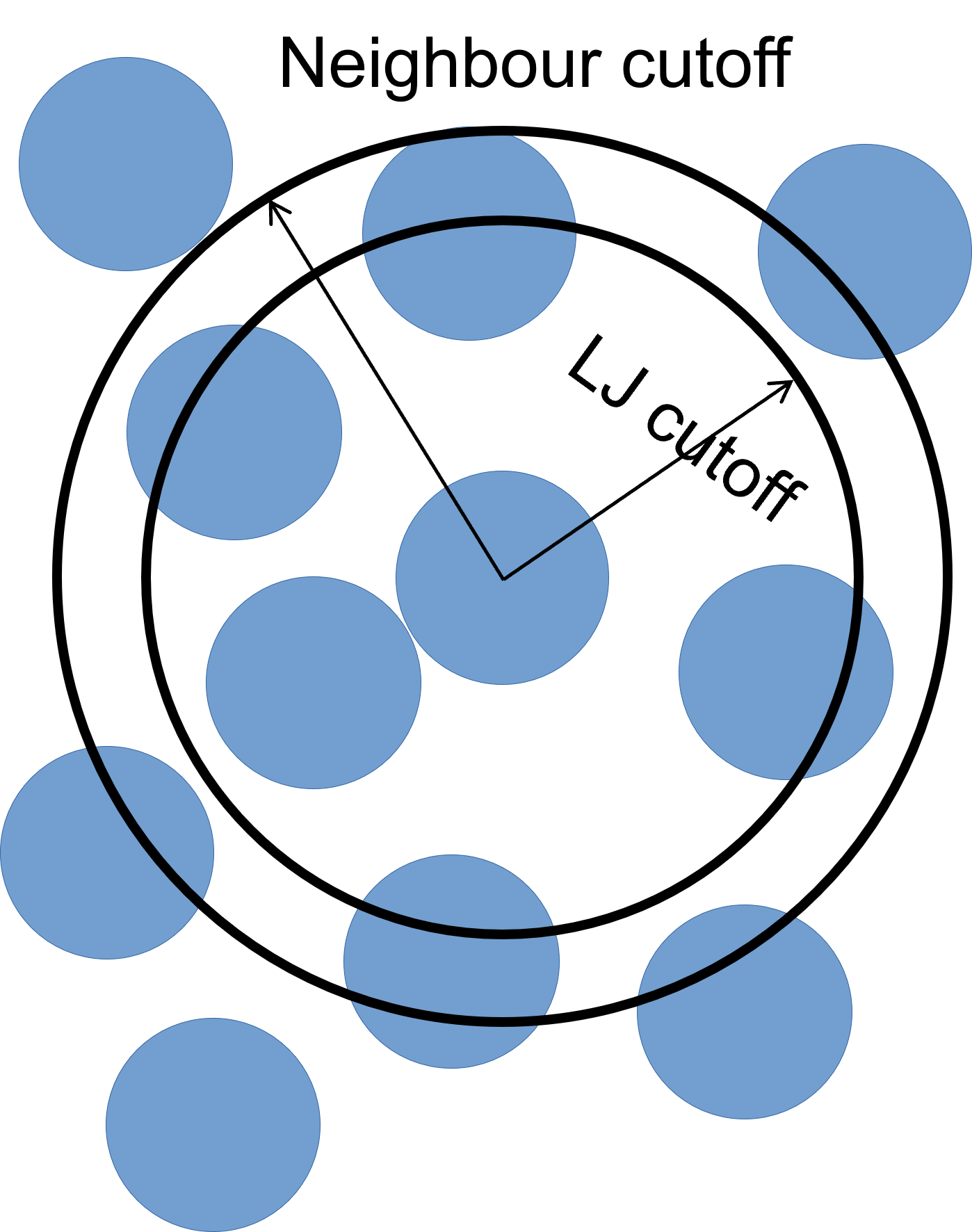

Neighbour lists

To improve simulation performance, and because we are truncating interactions at a certain distance, we can keep a list of particles that are close to each other (under a neighbour cutoff distance). This reduces the number of comparisons needed per time-step, at the cost of a small amount of memory.

We can set our neighbour list cutoff to be 0.3σ greater than our LJ cutoff (so a total of 3.8σ) – remember that, as we are dealing with spheres, a small increase in radius results can result in a large volume increase.

The bin keyword refers to the algorithm used to build the list,

bin is the best performing one for systems with homogeneous sizes of particles,

but there are others.

neighbor 0.3 bin

These lists still need to be updated periodically.

Provided that we rebuild them more frequently than the minimum time it takes for a particle to move from within the neighbour cutoff to outside of it.

We use the neigh_modify command to set the wait time between each neighbour list rebuild:

neigh_modify delay 10 every 1

The delay parameter sets the minimum number of time-steps that need to pass since the last neighbour list rebuild for LAMMPS to even consider rebuilding it again.

The every parameter tells LAMMPS to attempt to build the neighbour list if the number of timesteps since the delay ended is equal to the every value

– by default, the rebuild will only be triggered if an atom has moved more than half the neighbour skin distance (the 0.3 above).

How to set neighbour list delays?

You can estimate the frequency at which you need to rebuild neighbour lists by running a quick simulation with neighbour list rebuilds every timestep:

neigh_modify delay 0 every 1 check yesand looking at the resultant LAMMPS neighbour list information in the log file generated by that run.

The Neighbour list builds tells you how often neighbour lists needed to be rebuilt. If you know how many timesteps your short simulation ran for, you can estimate the frequency at which you need to calculate neighbour lists by working out how many steps there are per rebuild on average. Provided that your update frequency is less than or equal to that, you should see a speed up.

Simulation parameters

Now that we’ve set up the initial conditions for the simulation, and changed some settings to make sure it runs a bit faster, all that is left is telling LAMMPS exactly how we want the simulation to be run. This includes, but is not limited to, what ensemble to use (and which particles to apply it to), how big the time-step is, how many time-steps we want to simulate, what properties we want as output, and how often we want those properties logged.

The fix command has a myriad of options,

most of them related to ‘setting’ certain properties at a value,

or in an interval of values for one, all, or some particles in the simulation.

The first keywords are always ID – a name to reference the fix by, and group-ID – which particles to apply the command to.

The most common option for the second keyword is all.

fix 1 all nvt temp 1.00 1.00 5.0

Then we have the styles plus the arguments.

In the case above, the style is nvt, and the arguments are the temperatures at the start and end of the simulation run (Tstart and Tstop),

and the temperature damping parameter (Tdamp), in time units.

Setting the Nose-Hoover damping parameter

A Nose-Hoover thermostat will not work well for arbitrary values of

Tdamp. IfTdampis too small, the temperature can fluctuate wildly; if it is too large, the temperature will take a very long time to equilibrate. A good choice for many models is aTdampof around 100 time-steps. Note that this is NOT the same as 100 time units for most units settings.

Another example of what a fix can do, is set a property (in this case, momentum), to a certain value:

fix LinMom all momentum 50 linear 1 1 1 angular

This zeroes the linear momenta of all particles in all directions, as well as ensuring that the angular momentum remains constant at zero throughout the run.

Final setup

Although we created a number of particles in a box, if we were to run a simulation, not much would happen,

because these particles do not have any starting velocities.

To change this, we use the velocity command, which generates an ensemble of velocities for the particles in the chosen group (in this case, all):

velocity all create 1.0 199085 mom no

The arguments after the create style are the temperature and seed number.

The mom no keyword/value pair prevents LAMMPS from zero-ing the linear momenta from the system.

Then we set the size of the time-step, in whatever units we have chosen for this simulation – in this case, LJ units.

timestep 0.005

The size of the time-step is a careful juggling of speed and accuracy. A small time-step guarantees that no particle interactions are missing, at the cost of a lot of computation time. A large time-step allows for simulations that probe effects at longer time scales, but risks a particle moving so much in each time-step, that some interactions are missed – in extreme cases, some particles can ‘fly’ right through each other. The ‘happy medium’ depends on the system type, size, and temperature, and can be estimated from the average diffusion of the particles.

The next line sets what thermodynamic information we want LAMMPS to output to the terminal and the log file.

thermo_style custom step temp etotal pe ke press vol density

There are several default styles, and the custom style allows for full customisation of which fields and in which order to write them.

To set the frequency (in time-steps) at which these results are output, you can vary the thermo command:

thermo 500

In this case, an output will be printed every 500 time-steps.

To force LAMMPS to use the Verlet algorithm (rather than the default velocity-Verlet), we use:

run_style verlet

And finally, we choose how many time-steps (not time-units) to run the simulation for:

run 50000

Run LJ simulation

What command does it take to submit the LJ simulation to the ARCHER2 queue? What was the output?

Solution

sbatch sub.slurmWe will inspect the logfile in detail on the next session.

Key Points

Molecular dynamics simulations are a method to analyse the physical movement of a system of many particles that are allowed to interact.

A LAMMPS input file is a an ordered collection of commands with both mandatory and optional arguments.

To successfully run a LAMMPS simulation, an input file needs to cover basic simulation setup, read/create a system topology, force-field, and type/frequency of outputs.