Content from Introduction

Last updated on 2025-02-14 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 35 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is green software use and what does it mean for me as a user of HPC?

- What research activities produce carbon emissions?

Objectives

- Define green software use on HPC systems

- Appreciate emissions from HPC in the wider context of other research activities

- Understand that research and use of HPC can also have positive emissions impacts

What is green software?

Green software is an emerging discipline at the intersection of climate science, software design, electricity markets, hardware, and data center design.

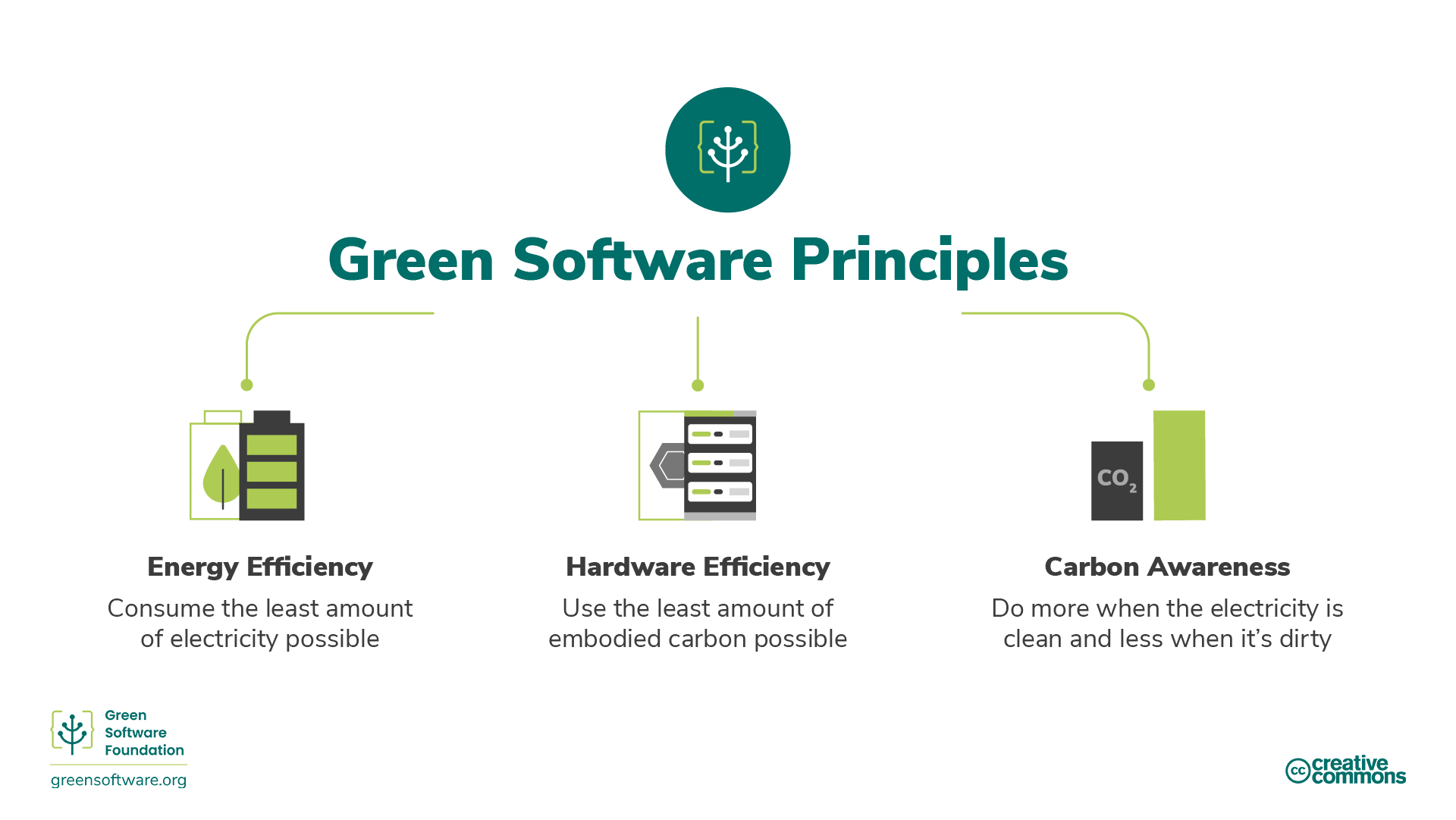

Green software use is carbon-efficient software use, meaning it emits the least carbon possible. Only three activities reduce the carbon emissions of software; energy efficiency, carbon awareness, and hardware efficiency.

This workshop will explain all of these concepts, how to apply them to use cases on high-performance computing (HPC) systems and how to measure them, as well as some of the international guidelines and organisations that guide and monitor this space.

Who is this aimed at?

Anyone involved in using HPC resources - either as a user, a developer of software for use on HPC or even professionals. By studying these principles, you will be able to better understand the effect of their use of HPC on carbon emissions, where it fits with emissions from your other activities and what concrete actions you can take to reduce your emissions and the size of the impact from these reductions.

History of green software engineering

In 2019 the original eight principles of green software engineering were released. This 2022 update of the principles took on feedback received over the years, merging some principles and adding a new one regarding understanding climate commitments. The principles as they are written are aimed primarily at software engineers but they are more broadly applicable to anyone making use of digital infrastructure. In this course we specifically look at how they can be applied to use of HPC resources.

How to understand green software on HPC

In this workshop, we cover the covers 6 key areas of green use of HPC (based on the principles of green software engineering):

- Carbon Efficiency: Emit the least amount of carbon possible.

- Energy Efficiency: Use the least amount of energy possible.

- Carbon Awareness: Do more when the electricity is cleaner and do less when the electricity is dirtier.

- Hardware Efficiency: Use the least amount of embodied carbon possible.

- Measurement: What you can’t measure, you can’t improve.

- Climate Commitments: Understand the exact mechanism of carbon reduction.

Each of these episodes will introduce some new concepts and explain in detail why they are important in terms of the climate, and how you can apply them in your work on HPC systems. We will use the ARCHER2 UK National Supercomputing Serivce to provide concrete examples of how the principles can be applied.

Principles, Patterns, and Practices.

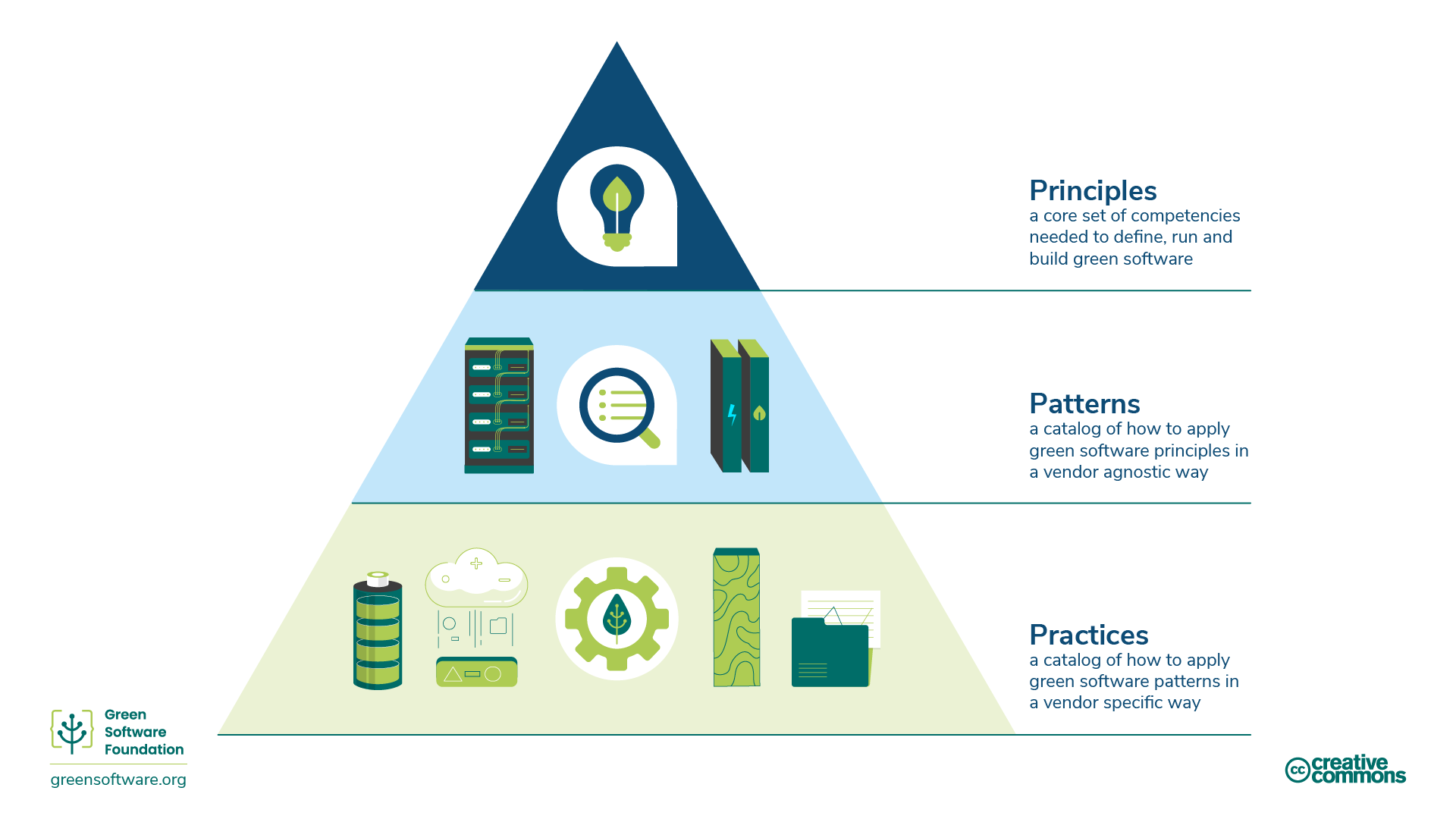

Above, we described the principles of green software, a core set of competencies needed to define, build and run green software. To support software engineers in this area, The Green Software Foundation has developed a catalogue of green software patterns. While not specific to use of HPC and aimed at software developers rather than users, they provide interesting information on how particular software types and their use can be made more environmentally sustainable.

A green software pattern is a specific example of how to apply one or more principles in a real-world example. Whereas principles describe the theory that underpins green software, patterns are the practical advice software practitioners can use in their software applications today. Patterns are vendor-neutral.

A green software practice is a pattern applied to a specific vendor’s product and informs practitioners about how to use that product in a more sustainable way.

Practices should refer to patterns that should refer to principles.

The green software foundation publishes a catalog of vendor-neutral green software patterns across various categories.

Other research activities

Use of HPC will be only one part of your research activities and may not even be the largest source of carbon emissions (though this does not mean you should not work to make your use of HPC more carbon efficient!). As well as understanding your carbon emissions from HPC, which this workshop will help you do, you also need to assess other activities you undertake as part of your research and try to estimate emissions associated with them.

Exercise: What does your research look like?

Write down the activities that you do as part of your research that could be a source of carbon emissions other than use of HPC. Once you have them written down, can you rank them in order of what you think the largest source of emissions will be to the smallest?

You may have come up with activities from the following list:

- Travel to/from place of work

- Travel to conferences, training and meetings

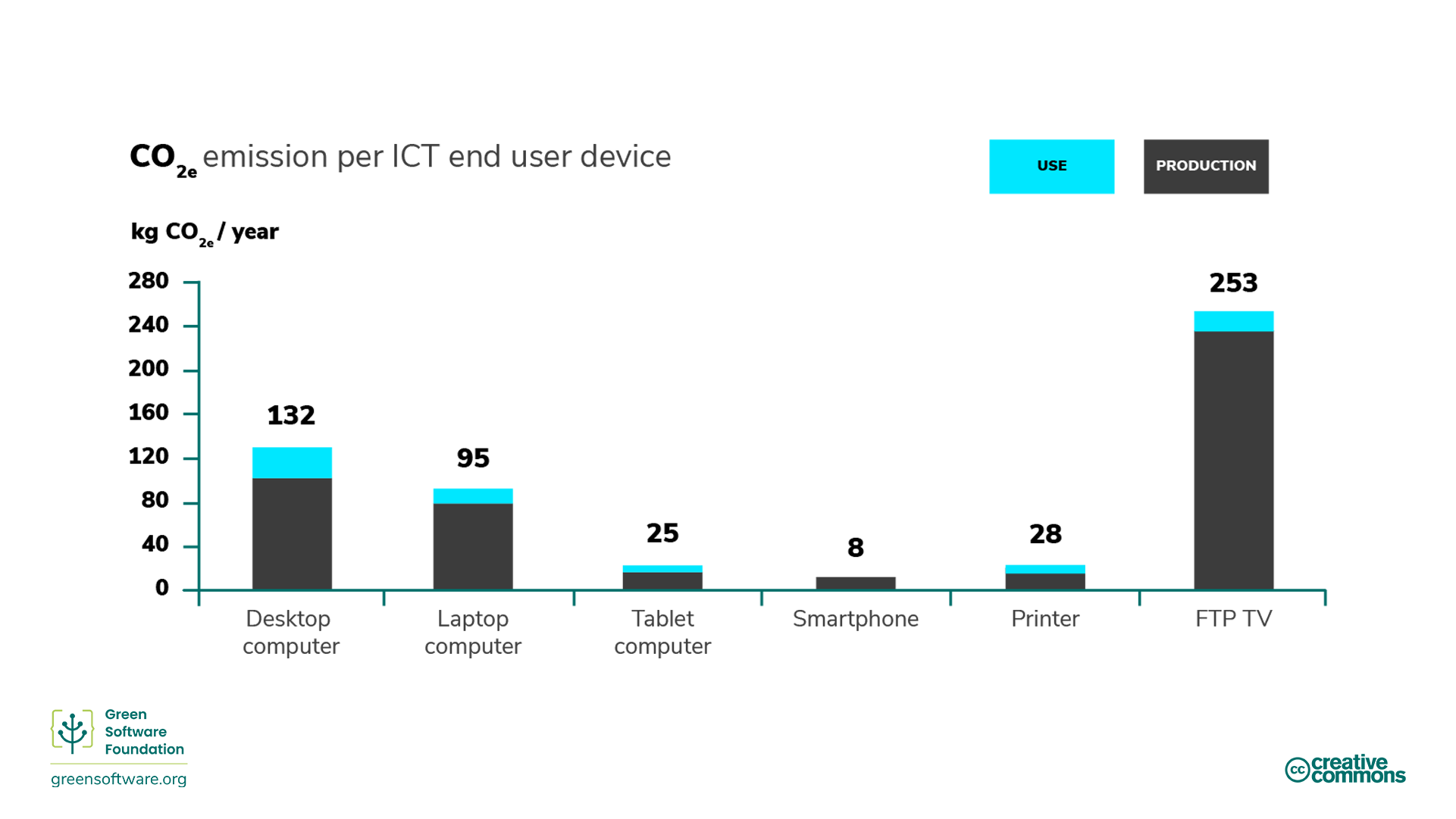

- Use of other computing resources (e.g. laptops/workstations, cloud resources and the internet)

- Laboratory work - chemicals, instruments

- Printed materials - books, journal articles

In fact, all activities that we undertake as part of our research produce carbon emissions. While, in an ideal world, we would be able to reduce emissions from all our activities we have finite time and effort so need to prioritise based on which reduction strategies will have the largest impact. This means that the first step is to estimate the emissions from different activities we are involved in as part of our research, even if the estimate is very rough.

- Travel emissions calculator (Deloitte UK)

- Emissions from laptops (Circular Computing)

- Transparent reporting of research-related greenhouse gas emissions through the scientific CO2nduct initiative

- Quantifying the carbon footprint of clinical trials: guidance development and case studies

- Emissions measurement and reporting approaches for the public sector (UK Government)

Key Points

- This course covers green software principles applied to HPC system use

- Carbon Efficiency: Emit the least amount of carbon possible.

- Energy Efficiency: Use the least amount of energy possible.

- Carbon Awareness: Do more when the electricity is cleaner and do less when the electricity is dirtier.

- Hardware Efficiency: Use the least amount of embodied carbon possible.

- Measurement: What you can’t measure, you can’t improve.

- Climate Commitments: Understand the exact mechanism of carbon reduction.

Content from Carbon Efficiency

Last updated on 2025-02-14 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is the difference between global warming and climate change?

- What is the difference between climate and weather?

- What are greenhouse gases (GHGs)?

- What does the term carbon equivalence (CO2e) mean?

- How is climate change monitored and reported?

Objectives

- Understand key terms in environmental sustainability.

- Understand what CO2e means.

- Understand how changes in the climate are monitored.

Introduction

Understanding the impact of greenhouse gases on our environment is key to understanding HPC’s own carbon footprint. You will learn about the different kinds of greenhouse gases present in the environment, how they are emitted and measured, and what is being done by different organisations around the world to control and reduce these emissions.

You will find out about the GHG protocol and what it means for green use of HPC.

Key concepts

Global warming vs climate change

Global warming is the long-term heating of Earth’s climate system observed since the pre-industrial period (between 1850 and 1900) due to human activities, primarily fossil fuel burning. Climate change is long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. These shifts may be natural, but since the 1800s, human activities have been the main driver of climate change.

Climate vs weather

Weather refers to the conditions of the atmosphere in a short period of time. Climate refers to the conditions of the atmosphere over long periods of time. Any changes to the long-term condition of the atmosphere will also cause changes to the short-term conditions. Some examples of measurable changes to weather conditions due to climate change are:

- Changes to the water cycle, including rainfall

- Melting of ice

- Heating of the land, air, and ocean

- Changes in ocean currents, acidity, and salinity

These changes can lead to flooding - both in coastal areas and due to increased rainfall - drought, wildfires and more frequent extreme weather conditions.

Greenhouse gases and the greenhouse effect

Greenhouse gases are a group of gases that trap heat from solar radiation in the Earth’s atmosphere. These gases act as a blanket, increasing the temperature on the surface of the Earth. This is a natural phenomenon which has been accelerated due to man-made carbon emissions. Now the global climate is changing at a faster rate than that at which animals and plants can adapt.

Greenhouse gases and the greenhouse effect are crucial to all life on Earth and often come from natural sources like animals, volcanoes, and other geological activity. The greenhouse effect allows the Earth to maintain a higher temperature than it would without them by capturing more heat from solar radiation. Like many other natural processes of the Earth, the greenhouse effect is a balance that can be upset by multiple factors.

Carbon and CO2e

Carbon is often used as a broad term to refer to the impact of all types of emissions and activities on global warming. CO2e (sometimes: CO2eq/CO2-eq), which stands for carbon equivalence, is a measurement term used to measure this impact. For example, 1 ton of methane has the same warming effect as about 84 tons of CO2 over 20 years, so we normalise it to 84 tons CO2e. We may shorten even further to just carbon, which is a term often used to refer to all GHGs.

Monitoring climate change

As a result of the effects of climate change and an ever-increasing number of destructive weather events, efforts have been made by the global community to address these issues and take steps to control and limit global warming in order to mitigate and reverse the effects of climate change.

The Paris Climate Agreement is an international treaty agreed in 2015 by 196 parties and the UN to reduce the Earth’s temperature increase. The agreement is to keep the rise in global mean temperature to 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels, with a preferable lower limit of 1.5°C. The agreement is reviewed every five years and mobilizes finance to developing nations to mitigate the impacts of climate change and prepare for and adapt to the environmental effects caused by climate change. In addition, each party is expected to update its progress through a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). As of October 2024, 195 parties, including the UK, have joined the agreement.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a group created to achieve the stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous interference with the climate system.

The COP (Conference of the Parties) is an annual event involving all parties in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. At the conference, each party member’s progress on tackling global warming, as agreed as part of the Paris Climate Agreement, is reviewed and assessed. The COP is also a chance for parties to come together and make decisions that will reduce the effects of global warming. Common topics include strategies to reduce carbon, financing low carbon strategies and preservation of natural habitats.

The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), created by the UN in 1988, aims to provide governments at all levels with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies. IPCC reports are also a key input into international climate change negotiations. The IPCC is an organization of governments that are members of the United Nations or the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The IPCC currently has 195 members.

We will always emit carbon through our activities, but being carbon efficient means minimising the amount of carbon emitted per unit of work. We aim to ensure that for each gram of carbon we emit into the atmosphere, we extract the most value possible.

In the HPC space, the part we play in the climate solution is using HPC in a carbon efficient way. Being carbon efficient is about making sure your use of HPC emits the least carbon possible for the work we are doing. Or, for providers of HPC systems, it means procuring and operating the system in such a way as to minimise the carbon emissions. Ideally, you would also be able to quantify the positive carbon impacts from the work (or HPC system itself) to understand the overall net impact on carbon emissions - though doing this is typically quite challenging.

Positive emissions impacts

As well as reducing emissions from our use of HPC there are typically other sources of positive carbon emissions impact associated with HPC

The main source of reduced emissions from HPC use is in the research that leads to new technology, policies and approaches to reducing emissions. Some examples include:

- HPC services run the climate models that are used to provide evidence for setting emissions reductions policies and targets across the world. Research and modelling on HPC services leads to development of improved zero emission energy generation by, for example, modelling new wind turbine and wind farm designs.

- Modelling to support the development of new energy storage technologies such as improved batteries.

The emissions reductions from such activities are extremely difficult to quantify for a number of reasons so, at the moment, these are not factored in to the emissions estimates for HPC systems and research more broadly but you should be aware of them and think about how they might apply to your research in particular.

As well as the research activities on HPC systems leading to reductions in emissions, there are other activities that HPC services can potentially take to have positive emissions impacts, for example:

- Using the waste heat generated by large scale HPC services as a heat source for homes, businesses or farming. For example, the LUMI HPC system in Finland is connected to the district heat network for the local city of Kaajani and helps heat homes and businesses.

- Incorporating environmental and biodiversity improvements into the service. For example, for the ACF data centre that hosts ARCHER2 (which is in a rural location) EPCC have been working to improve the site biodiversity and improve habitats.

- Responsible carbon offset schemes could also potentially be used to reduce emissions if they are undertaken as part of providing an HPC service.

Exercise: Positive emissions impacts

Write down the outcomes or activities that you do as part of your research or work that could be produce positive carbon emissions. Once you have them written down, can you rank them in order of what you think the largest source of emissions will be to the smallest? Can you think of any way in which you might go about quantifying this positive impact so it could be included in a carbon audit of your work?

You may have come up with outcomes such as:

Key Points

- Greenhouse gases are a group of gases contributing to global warming. Carbon is often used as a broad term to refer to the impact of all types of emissions and activities on global warming. CO2e is a measurement term used to measure this impact.

- The international community, in groups such as the UNFCCC, has come together to limit the impact of global warming by reducing emissions, aiming for a ‘preferable’ lower limit of 1.5°C. This was agreed through the UN IPCC in 2015 in the Paris Climate Agreement and is monitored at the regular COP event.

- Everything we do emits carbon into the atmosphere, and our goal is to emit the least amount of carbon possible. This constitutes the first principle of green software use: carbon efficiency, emitting the least amount of carbon possible per unit of work.

Content from Energy Efficiency

Last updated on 2025-01-13 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- TBC

Objectives

- TBC

Introduction

Energy is the ability to do work. There are many different forms of energy, such as heat, electrical and chemical, and one type of energy can be converted to another. For example, we convert chemical energy in coal to electrical energy. In other words, electricity is secondary energy converted from another energy type. In this way, we can think of energy as a measure of the electricity used.

All software, from large scale modelling and simulation on HPC, to the training of Machine Learning models, to the applications running on mobile phones consumes electricity. One of the best ways to reduce electricity consumption and the subsequent carbon emissions made by software is to make make our use of HPC facilities more energy efficient.

Callout

The use of low-carbon sources of electricity such as wind or hydroelectric also reduce the emissions from the electricity we consume by our use of HPC. However, even renewable electricity sources have a carbon cost from the manufacture, operation and decommissioning of the energy source (e.g. wind farm) so there are always reductions in emissions to be gained from reducing energy use. We will talk about how you estimate the impact of different emissions sources, including electricity use, later in this workshop so you can prioritise your effort where it will have the most impact.

The reduction of energy consumed by work on an HPC system depends on a lot of things, including:

- the design and algorithm choices of the software engineers who wrote the software;

- the technology of the HPC system itself;

- how the source code is interpreted by compilers to produce machine-executable code (including compiler optimisations);

- the input and setup of the software given by the user themselves.

All the different people involved at different stages can impact the energy efficiency of the use case on the HPC system. Some people will only be able to impact one aspect but many people are involved in more than one of these aspects. For example, most researchers using HPC systems make use of software (specifying inputs and specifying the parallel distribution of work) and also design and write their own software (even if this is analysis scripts in a language such as Python).

Collectively, we all take responsibility for the energy consumed by HPC systems and design them and the software that runs on them, and use the software on them to consume as little as possible. We should make sure that, at every step in the process, there is as little waste as possible.

Let’s take a look at some of these concepts and some ways that you can become more energy efficient at every stage.

Key concepts

Fossil fuels and high-carbon sources of energy

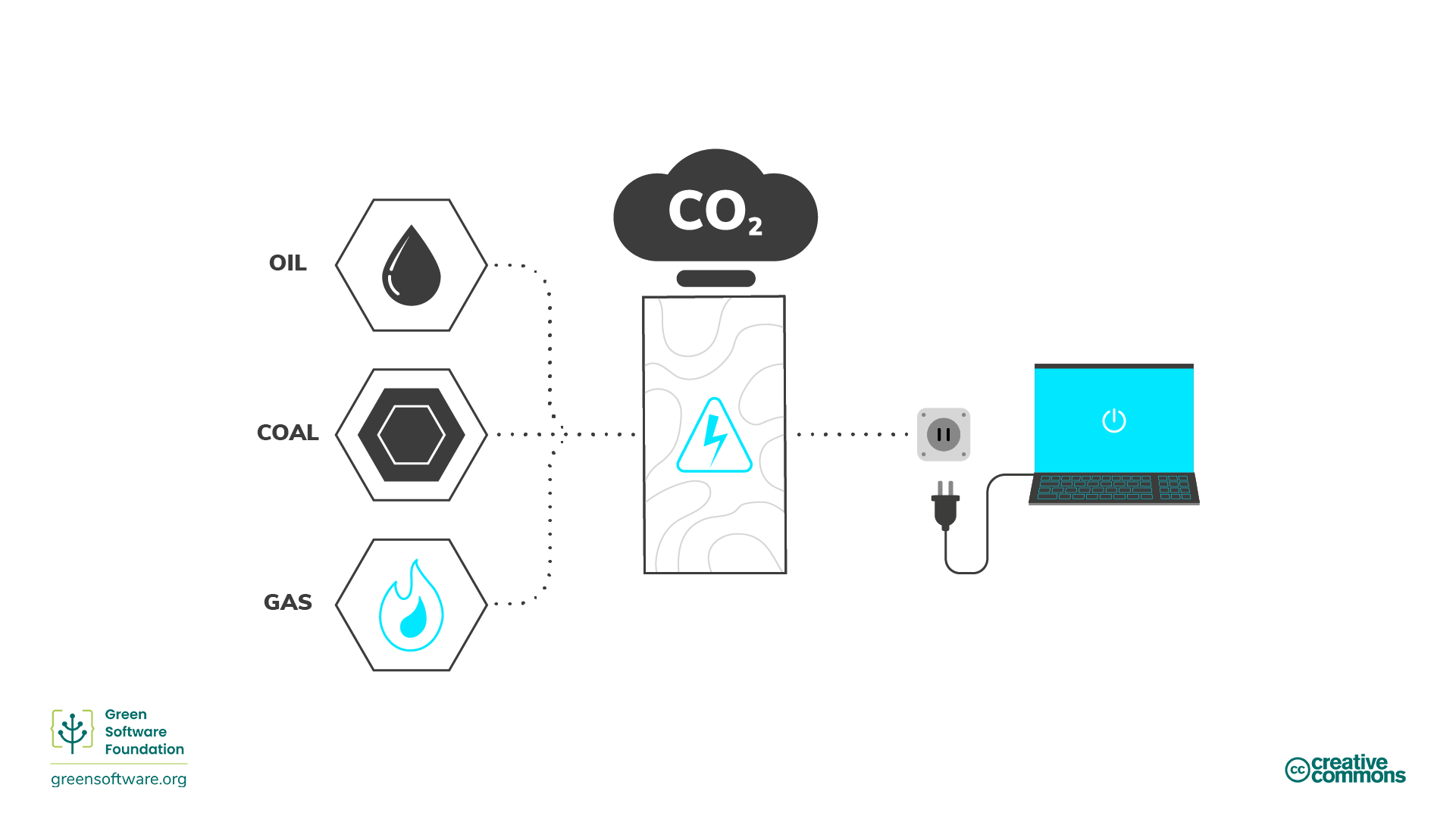

Across the world, a lot of electricity is produced through burning fossil fuels, usually coal. Fossil fuels are made from decomposing plants and animals. These fuels are found in the Earth’s crust and contain carbon and hydrogen, which can be burned for energy. Coal, oil, and natural gas are examples of fossil fuels.

Most people think electricity is clean. Our hands don’t get dirty when we plug something into a wall, and our laptops don’t need exhaust pipes. However, in some geographical regions most electricity comes from burning fossil fuels and energy supply is the single most significant cause of carbon emissions. For HPC services hosted in such locations, we can draw a direct line from electricity to carbon emissions and, hence, electricity can be considered a proxy for carbon. If our goal is to be carbon efficient in out use of HPC hosted in these regions, then it means our goal is also to be energy efficient since energy is a proxy for carbon. This means using the least amount of energy possible per unit of work.

In the UK (where ARCHER2 is housed) GHG emissions from energy generation in 2023 make up 11.5% of total emissions. The emissions from electricity generation have dropped by over 78% from 1990 to 2023. (Data from UK Government: 2023 UK greenhouse gas emissions, provisional figures.) In locations where electricity generation is decarbonising so quickly, measuring electricity use from our use of HPC and using it as proxy for carbon does not make as much sense as for regions where electricity generation has a high carbon intensity. Reducing electricity use is still part of the goal of greener use of HPC but other (embodied) sources of emissions become more important. We will discuss this later in this workshop.

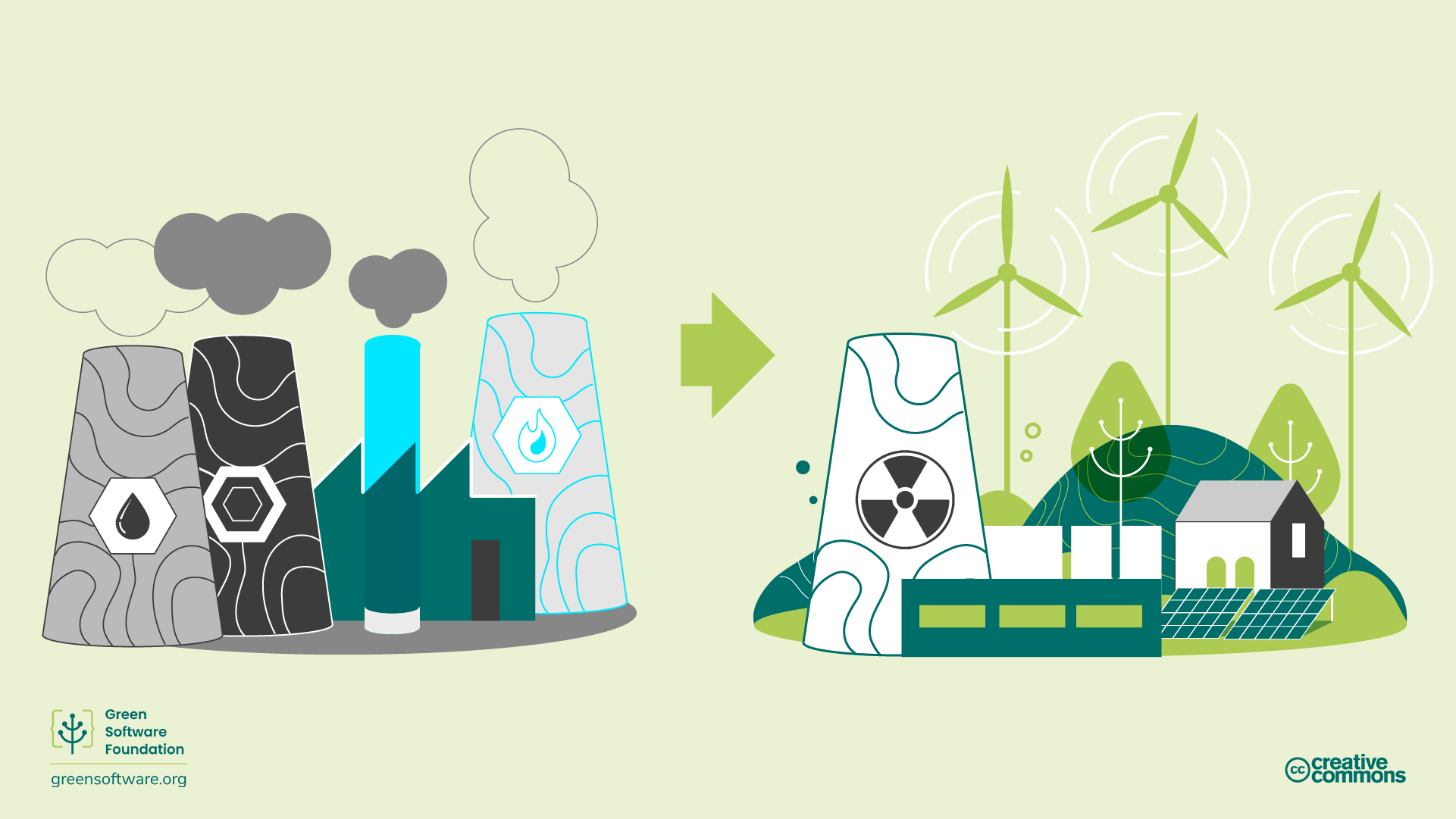

Low-carbon sources of energy

Clean energy comes from renewable, zero-emission sources that do not pollute the atmosphere when used and save energy through energy-efficient practices. There are overlaps between clean, green, and renewable energy. Here’s how we can differentiate between them:

- Clean energy - doesn’t produce carbon emissions e.g. nuclear.

- Green energy - sources from nature

- Renewable energy - sources will not expire e.g. solar, wind

Energy measurement

- Energy is measured in joules (J), the SI unit of energy.

- Power is measured in watts, where 1 watt (W) is a rate corresponding to one joule per second.

- A kilowatt (kW) is, therefore, also a rate corresponding to 1000 joules per second.

- A kilowatt-hour (kWh) is an alternative measure of energy (that is commonly used instead of J) corresponding to one kilowatt of power sustained for one hour.

How to improve energy efficiency

Now that we know how energy is produced and the associated cost in terms of emissions, based on whether low- or high-carbon energy sources are used, let’s take a look at some of the ways energy efficiency can be improved on HPC systems. Understanding power usage effectiveness and energy proportionality means you can make better decisions in terms of how to use energy in the most efficient way possible and waste less.

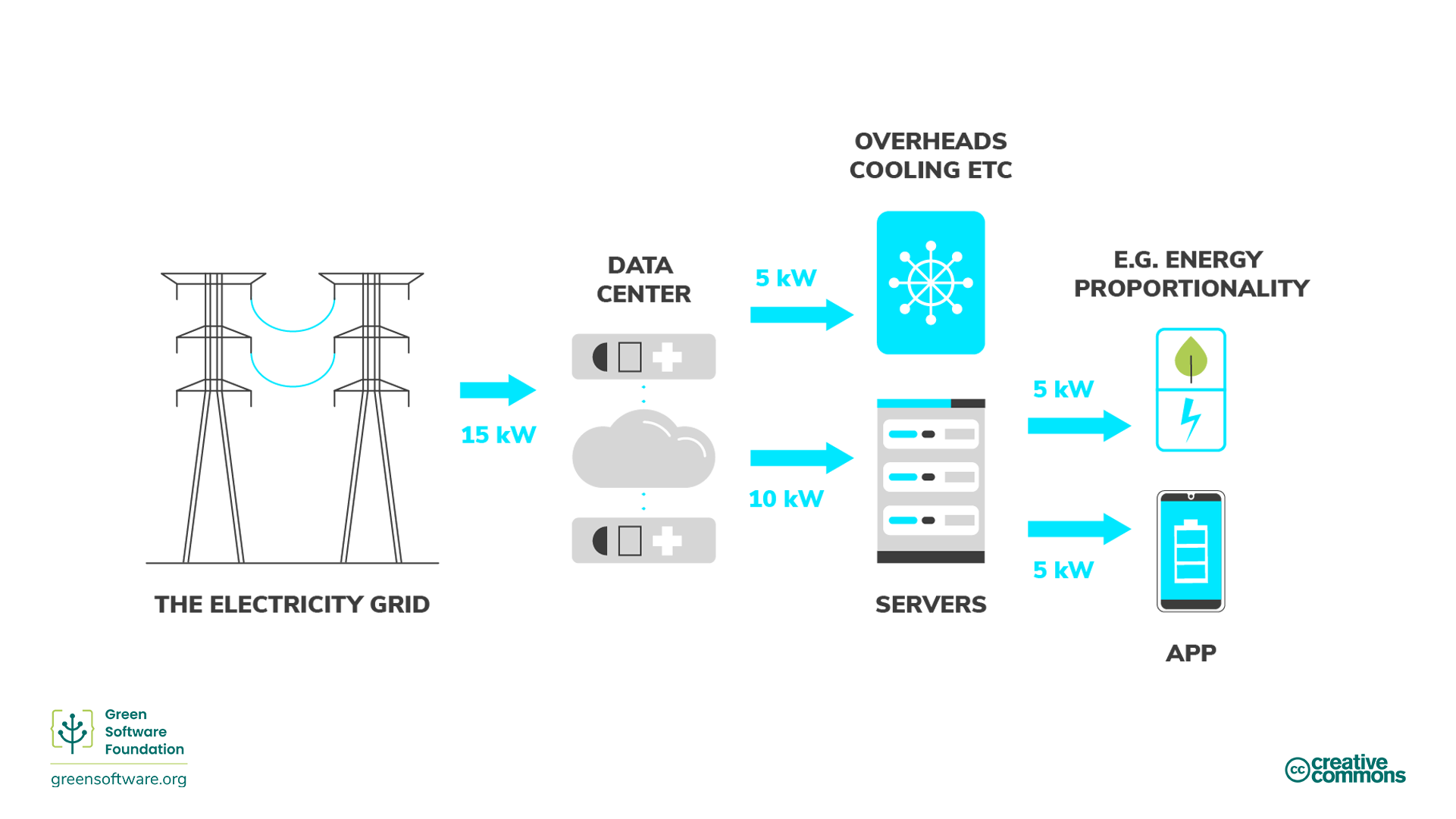

Power usage effectiveness

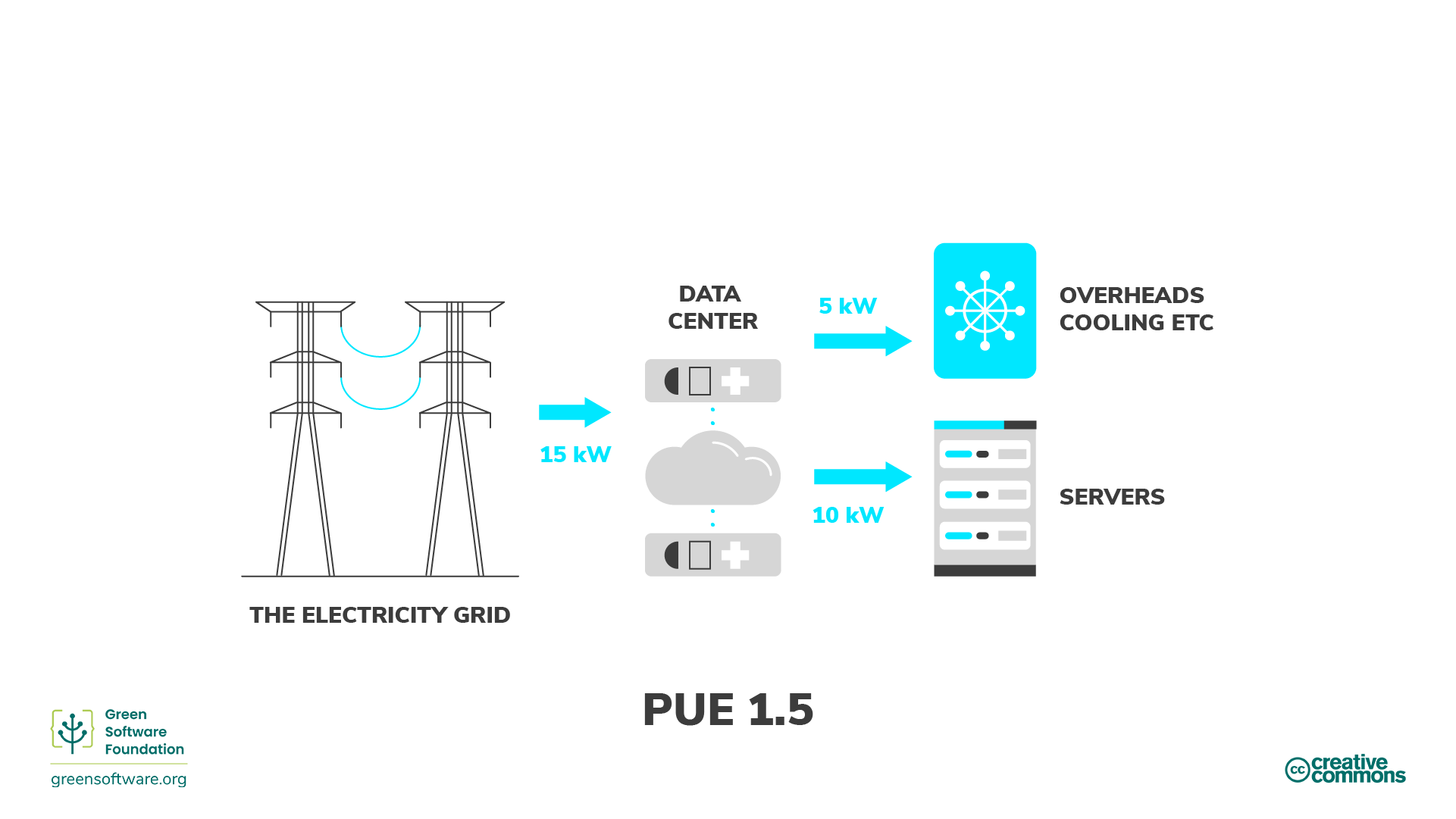

The data center industry uses the power usage effectiveness (PUE) metric, developed by Green Grid in 2006, to measure data center energy efficiency. Specifically, this relates to how much energy the computing equipment uses as compared to cooling and other overheads supporting the equipment. When a data center’s PUE is close to 1.0, computing is using nearly all energy. When the PUE is 2.0, this means an additional watt of power is required to cool and distribute power to the HPC equipment for every watt of HPC power it uses.

Another way to think of PUE is as a multiplier to your energy consumption when using HPC. So, for example, if your use consumed 10 kWh and the PUE of the data center where it is running is 1.5, then the actual consumption from the grid is 15 kWh: 5kWh goes towards the operational overhead of the data center, and 10 kWh goes to the servers that are running your application.

In many cases, PUE is not constant over time for the data centres that host HPC systems. The PUE value often depends on how much energy is required to cool the system. This obviously varies with load (as the more work a system is doing, the more power it is drawing and the more cooling it requires) but it often also varies with atmospheric conditions - the cooler the air temperature is, the less additional power you need to draw to cool the HPC system. HPC systems hosted in cooler locations can often make use of “free cooling” where refrigeration technology is not required to cool the system, the outside air (or water) temperature is cool enough to do this without the need for mechanical cooling.

Callout

The PUE of the Advanced Data Centre (ACF) facility that hosts the ARCHER2 system in Edinburgh typically has a PUE of 1.1 as measured over a calendar year. As the ACF is situated in Scotland where air temperatures are cool, it benefits from free cooling for a large proportion of the year.

Energy proportionality

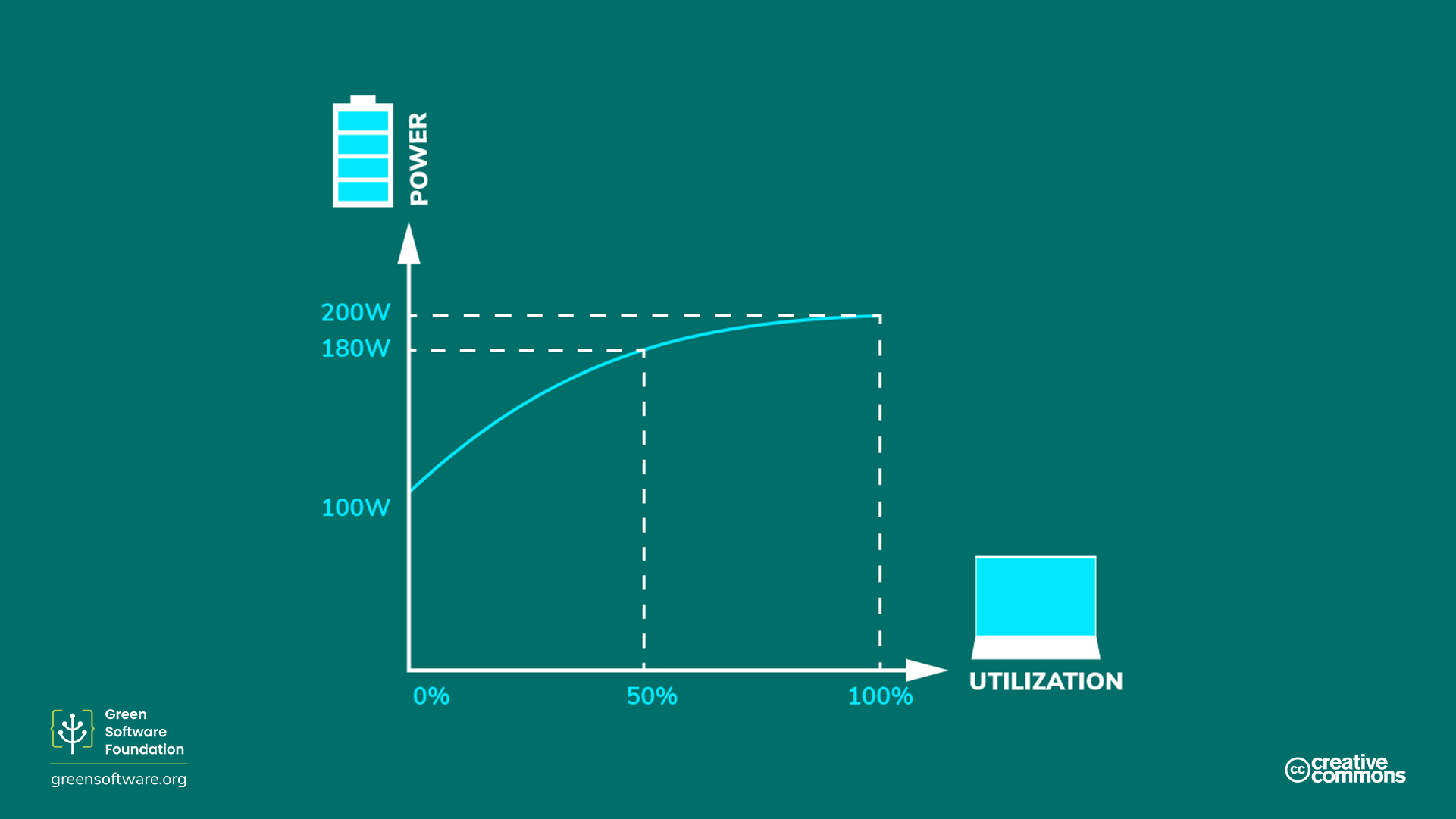

Energy proportionality, first proposed in 2007 by engineers at Google, measures the relationship between power consumed by a computer and the rate at which useful work is done (its utilisation).

Utilisation measures how much of a computer’s resources are used, usually given as a percentage. A fully utilised computer running at its maximum capacity has a high percentage, while an idle computer with no utilisation has a lower percentage.

The relationship between power and utilization is not proportional. Mathematically speaking, proportionality between two variables means their ratios are equivalent. For example, at 0% utilisation, a computer may draw 100 W; at 50%, it draws 180 W; and at 100%, it draws 200 W. The relationship between power consumption and utiliation is not linear and does not cross the origin.

Because of this, the more we utilise a computer, the more efficient it becomes at converting electricity to practical computing operations. One way to improve hardware efficiency is to run the workload on as few servers as possible, with the servers running at the highest utilisation rate, maximising energy efficiency.

However, the story for HPC use is actually less straightforward than this description. The energy proportionality argument holds when the performance of an application is compute bound - that is, when the output from the application you are running is strongly correlated with the performance of the processors (actually, for HPC, it is typically the performance of the floating point units in the processors). The performance of many HPC applications is actually memory-bound so the performance is dependent on the performance of data moving from memory to be processed. In these cases, once you are above a certain performance threshold for the floating point units any additional power draw does not lead to increased utilisation (i.e. useful performance for the application); the more you you utilise the processor, the more power you draw but you do not get any additional useful performance so this is just wasted electricity, reducing the energy efficiency of your use. It becomes even more complex as you run parallel applications (as typically happens on HPC resources) as the change in parallel distribution can change the balance between compute bound and memory bound performance for your application.

HPC application performance

Performance of HPC applications can be: compute-bound, memory-bound, IO-bound, communications-bound and the utilisation argument made above only really applies to applications where performance is strongly compute-bound. In reality, the performance of most HPC applications is bound by different limits at different stages in their execution (e.g. IO-bound while reading in large datasets, compute-bound while calculating) and so a theoretical analysis of how the energy consumption changes as a function of processor utilisation is difficult to perform.

Given this complexity, what practical steps can you take to decide on how to run in an energy-efficient manner on HPC systems? The answer is to run some test cases and measure the energy consumption and performance, then change parameters (such as processor power cap, or number of parallel processes) and measure again to see what the impact is on both performance and energy consumption. Using a benchmarking approach such as this, you can practically improve the energy efficiency of your use of HPC.

Static power draw

The static power draw of a computer is how much electricity is drawn when in an idle state. The static power draw varies by configuration and hardware components, but all parts have some static power draw. This is one of the reasons that PCs, laptops, and end-user devices have power-saving modes. If the device is idle, it will eventually trigger a hibernation mode and put the disk and screen to sleep or even change the CPU’s frequency. These power-saving modes save on electricity, but they have other trade-offs, such as a slower restart when the device wakes up.

HPC systems are usually not configured for aggressive or even minimal power saving when idle. Many use cases running on servers demand total capacity as quickly as possible because the server needs to respond to rapidly changing demands, which leads to many servers in idle modes during low-demand periods. An idle server has a carbon cost from both the embedded carbon as well as its inefficient utilisation. This is one reason why the goal of many HPC systems is to maximise utilisation.

Key Points

- In regions of high carbon intensity electricity production, electricity is a good proxy for carbon, so using HPC in an energy efficient way is equivalent to using HPC in a way that is carbon efficient.

- In regions of low carbon intensity electricity production, electricity is not a good proxy for carbon.

- Green HPC use takes responsibility for its electricity consumption and considers how this relates to carbon emissions.

- Quantifying the energy consumption of your HPC use is a step in the right direction to start thinking about how you can operate more efficiently. However, understanding the energy consumption of your use of HPC is not the only story. The hardware your software is running on uses some of the electricity for operational overhead. This is called power usage efficiency (PUE) for HPC systems (and for computing resources hosted in data centres more generally).

- The concept of energy proportionality adds another layer of complexity since hardware becomes more efficient at turning electricity into useful operations the more it’s used.

- Understanding this gives us a better insight into how your HPC use behaves with respect to energy consumption in the real world.

Content from Carbon Awareness

Last updated on 2025-01-13 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How does electricity generation affect GHG emissions?

- What is carbon instensity of electricity generation and how does it vary geographically and temporally?

- What techniques can I use to make my use of HPC greener and influence transition to low-carbon electricity generation?

Objectives

- Understand the concept of carbon intensity in electricity generation

- Appreciate the level of variation in carbon intensity across the UK and the world

- Understand techniques for greener use of HPC: demand shifting and demand shaping

Introduction

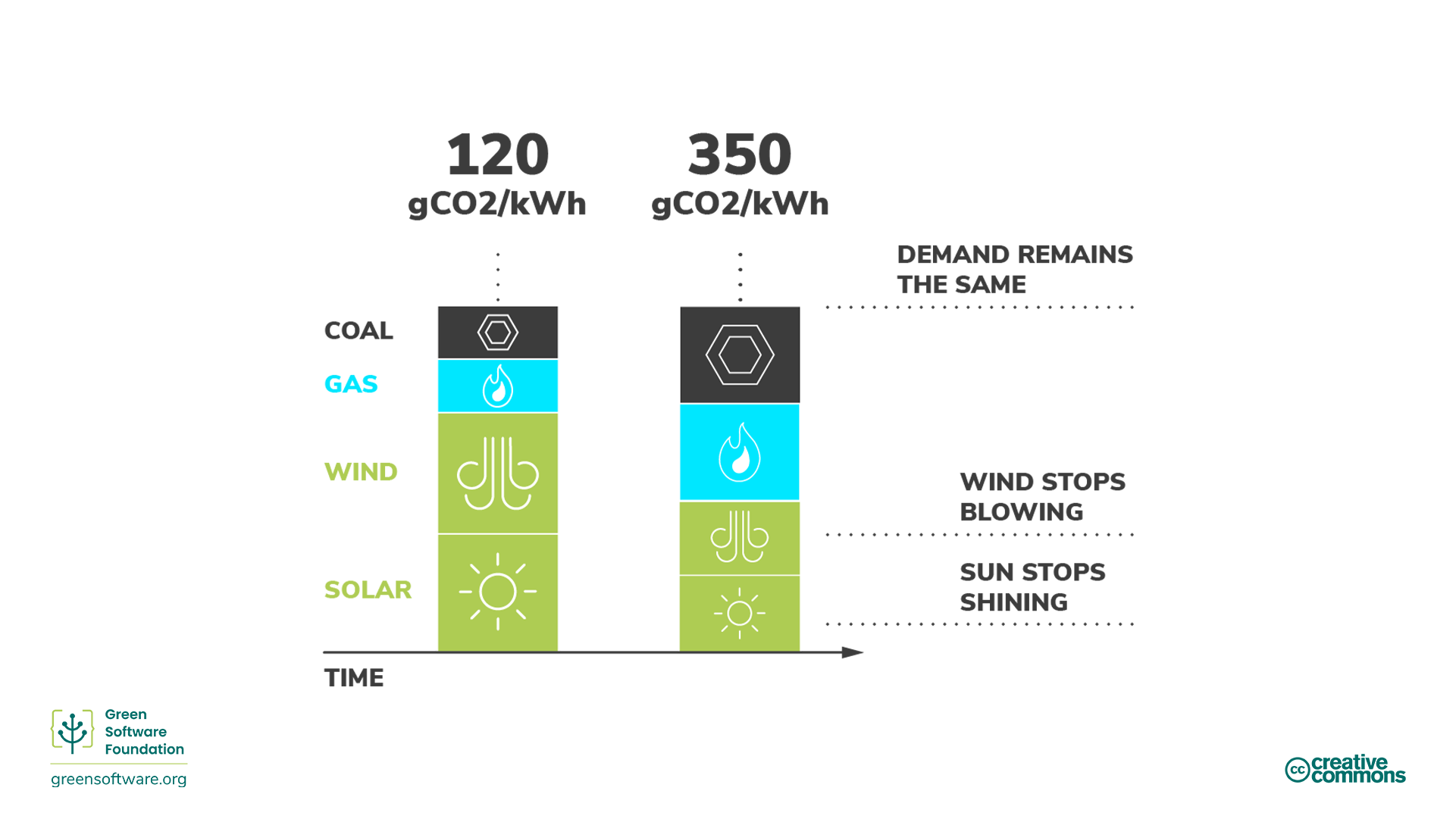

Not all electricity is produced in the same way. In different locations and times, electricity is generated using a variety of sources with varying carbon emissions. Some sources, such as wind, solar, or hydroelectric, are clean, renewable sources that emit little carbon. On the other hand, fossil fuel sources emit carbon at varying degrees to produce electricity. For example, both gas and coal emit more carbon than renewable sources, but gas-burning power plants emit less carbon than coal-burning power plants.

Carbon awareness is the idea of doing more when more energy comes from low carbon sources and doing less when more energy comes from high carbon sources.

Key concepts

Carbon intensity

Carbon intensity measures how much carbon (CO2e) is emitted per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity consumed. The standard unit of carbon intensity is gCO2e/kWh, or grams of carbon per kilowatt hour.

If your computer is plugged directly into a wind farm, its electricity would have a carbon intensity of 0 gCO2e/kWh since a wind farm emits no carbon to produce that electricity. However, most people can’t plug directly into wind farms; instead, they plug into power grids supplied with electricity from various sources.

Embodied carbon of renewable sources

In reality, the carbon intensity of renewable sources still have some GHG emissions associated with them from the emissions used to build, operate and decommission them. As we will se in a later episode, these emissions are usually amortised across the lifetime of the facility (in this case, the lifetime of the generation facility). By convention, these embodied emissions are not usually included in carbon intensity values for generated energy as they are complex to calculate and the emissions saved by replacing non-renewable sources with renewable sources have vastly outweighed the embodied emissions of renewable sources. These emissions sources will become a more important component of energy generation as electricity grids continue to decarbonise.

Once on a grid, you can’t control which sources supply the electricity you are using; you simply get a mix of everything. So, your carbon intensity will be a mix of all the current power sources in a grid, both the lower- and the higher-carbon sources.

Variability of carbon intensity

Carbon intensity varies by location since some regions have an energy mix containing more clean energy sources than others. This table shows the median carbon intensity for UK regions over 2024 (ref.):

| Region | Median Carbon Intensity (gCO2e/kWh) |

|---|---|

| S. Scotland | ??? |

Similarly, this table compares values across the world in 2023 (ref.):

| Country | Median Carbon Intensity (gCO2e/kWh) |

|---|---|

| UK | ??? |

Carbon intensity also changes over time due to the inherent variability of renewable energy caused by the unpredictability of weather conditions. For example, when it’s cloudy or the wind isn’t blowing, carbon intensity increases since more of the electricity in your mix comes from sources that emit carbon.

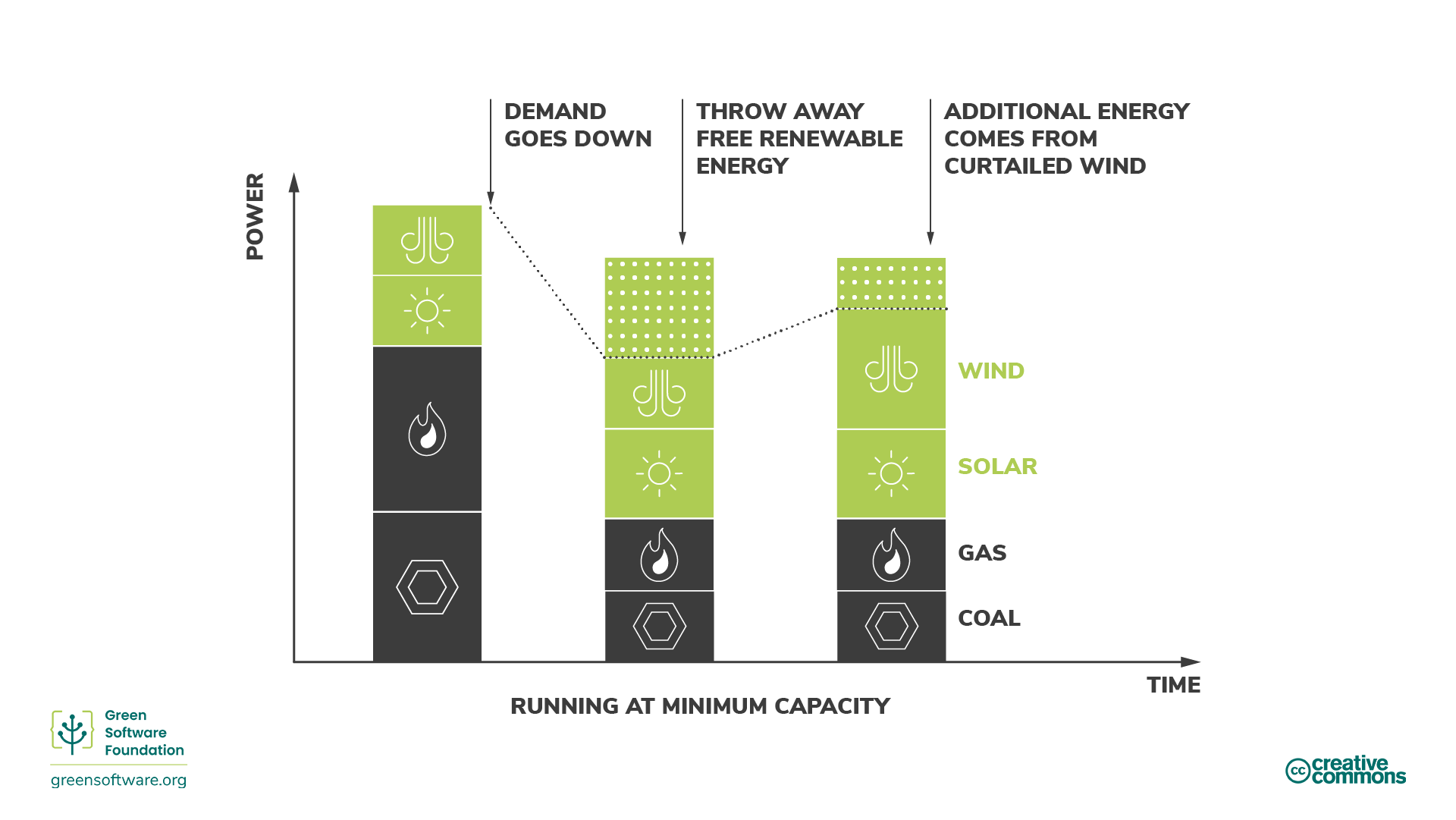

Dispatchability & curtailment

Electricity demand varies during the day and supply always needs to be able to meet that demand. A brownout (a dip in the voltage level of the power line) occurs if a utility doesn’t produce enough electricity to meet demand. Conversely, if a utility produces more electricity than is required, then to stop infrastructure burning out, breakers trip and we have blackouts.

There needs to be a balance between the demand and supply of electricity at all times and the responsibility for this usually falls to the utility provider.

In the case of fossil fuels such as coal, it is easier to control the power produced for this supply; this is called dispatchability. However, in the case of renewable power sources such as wind farms, the power produced cannot easily be controlled (we can’t control how much the wind blows). If the power source produces more electricity than is needed, that electricity is thrown away; this is called curtailment.

Marginal carbon intensity

If you suddenly need to access more power - for example, you need to turn on a light - that energy comes from the marginal power plant. The marginal power plant is dispatchable, which means marginal power plants are often powered by fossil fuels.

Marginal carbon intensity is the carbon intensity of the power plant that would have to be employed to meet any new demand.

Fossil-fueled power plants rarely scale down to 0. They have a minimum functioning threshold, and some don’t scale; they are considered a consistent, always-on baseload. Because of this, we sometimes have the scenario where we curtail (throw away) renewable energy while still consuming energy from fossil fuel power plants.

In these situations, the marginal carbon intensity will be 0 gCO2e/kWh since we know that any new demand will match the renewable energy we are curtailing.

Energy markets

The exact market model varies around the world but broadly follows the same model.

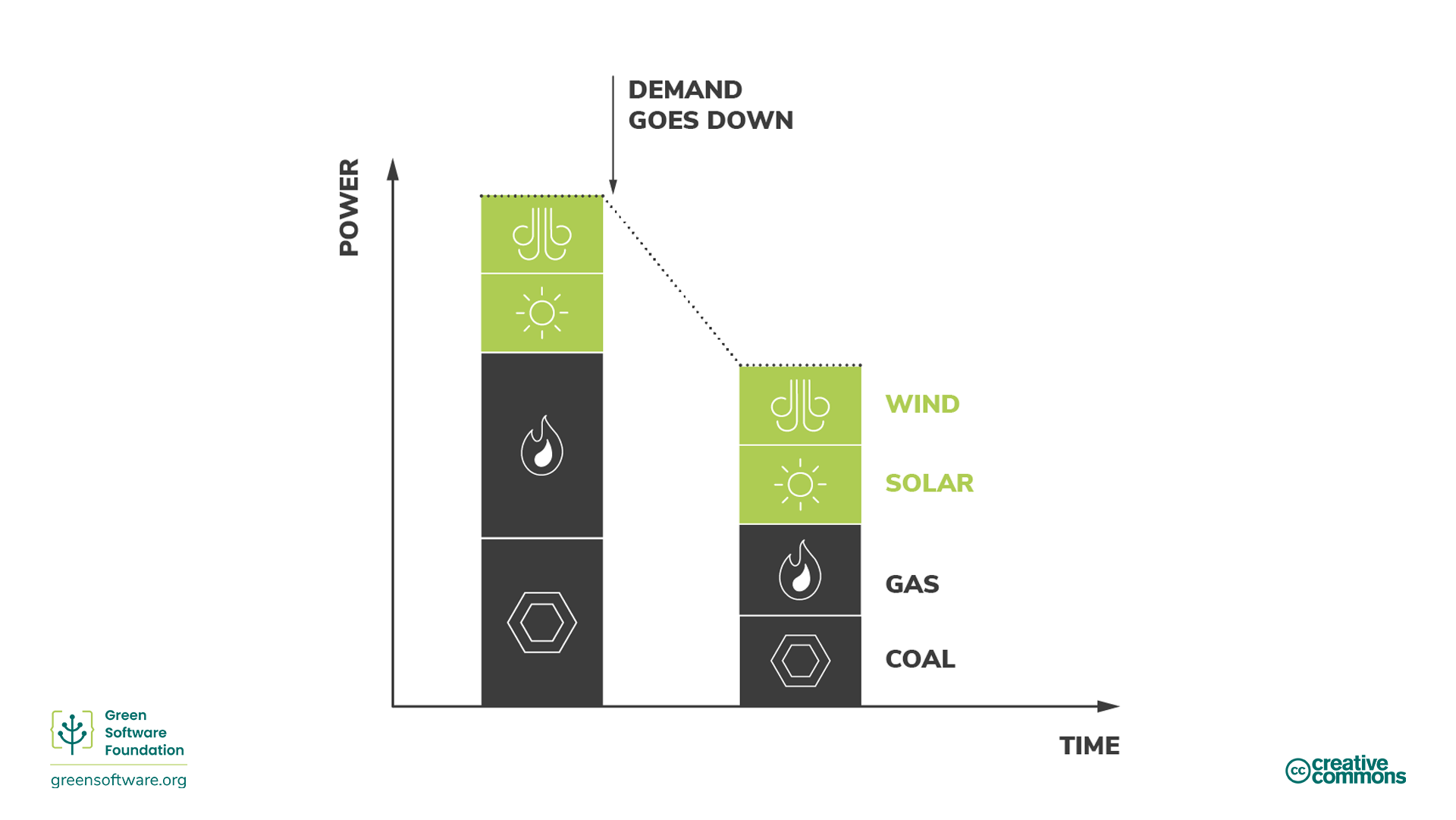

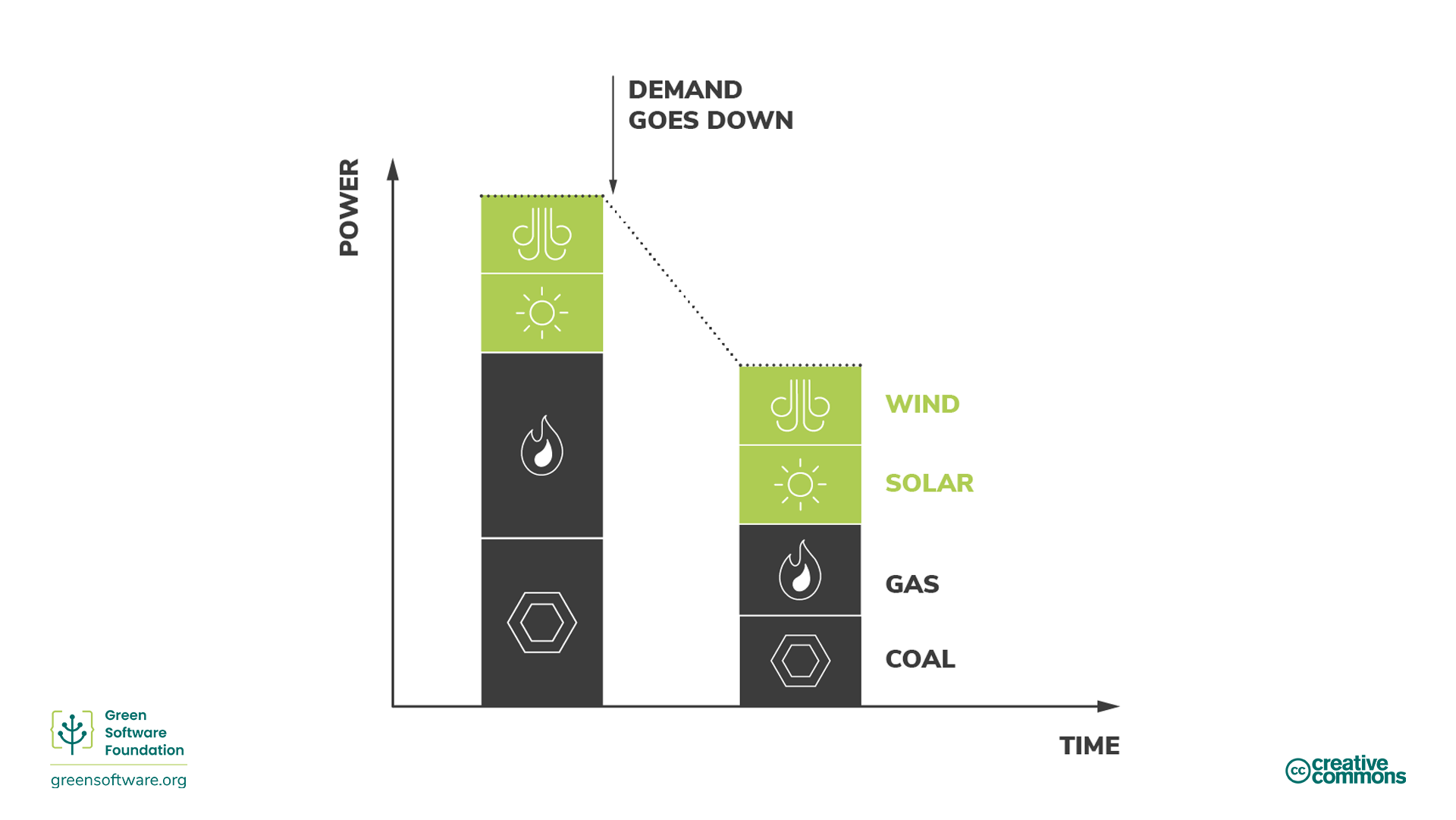

When the demand for electricity goes down, utilities need to reduce the supply to balance supply and demand. They can do this in one of two ways:

- Buy less energy from fossil fuel plants.

Energy from fossil fuel plants is usually the most expensive so this is

the preferred method. This directly translates to burning fewer fossil

fuels.

Energy from fossil fuel plants is usually the most expensive so this is

the preferred method. This directly translates to burning fewer fossil

fuels.

- Buy less energy from renewable sources.

Renewable sources are the cheapest, so they prefer not to do this. If a renewable source doesn’t manage to sell all of its electricity, it has to throw the rest away.

Reducing the amount of electricity consumed by your use of HPC can help decrease the energy’s carbon intensity as the first thing to be scaled back are fossil fuels.

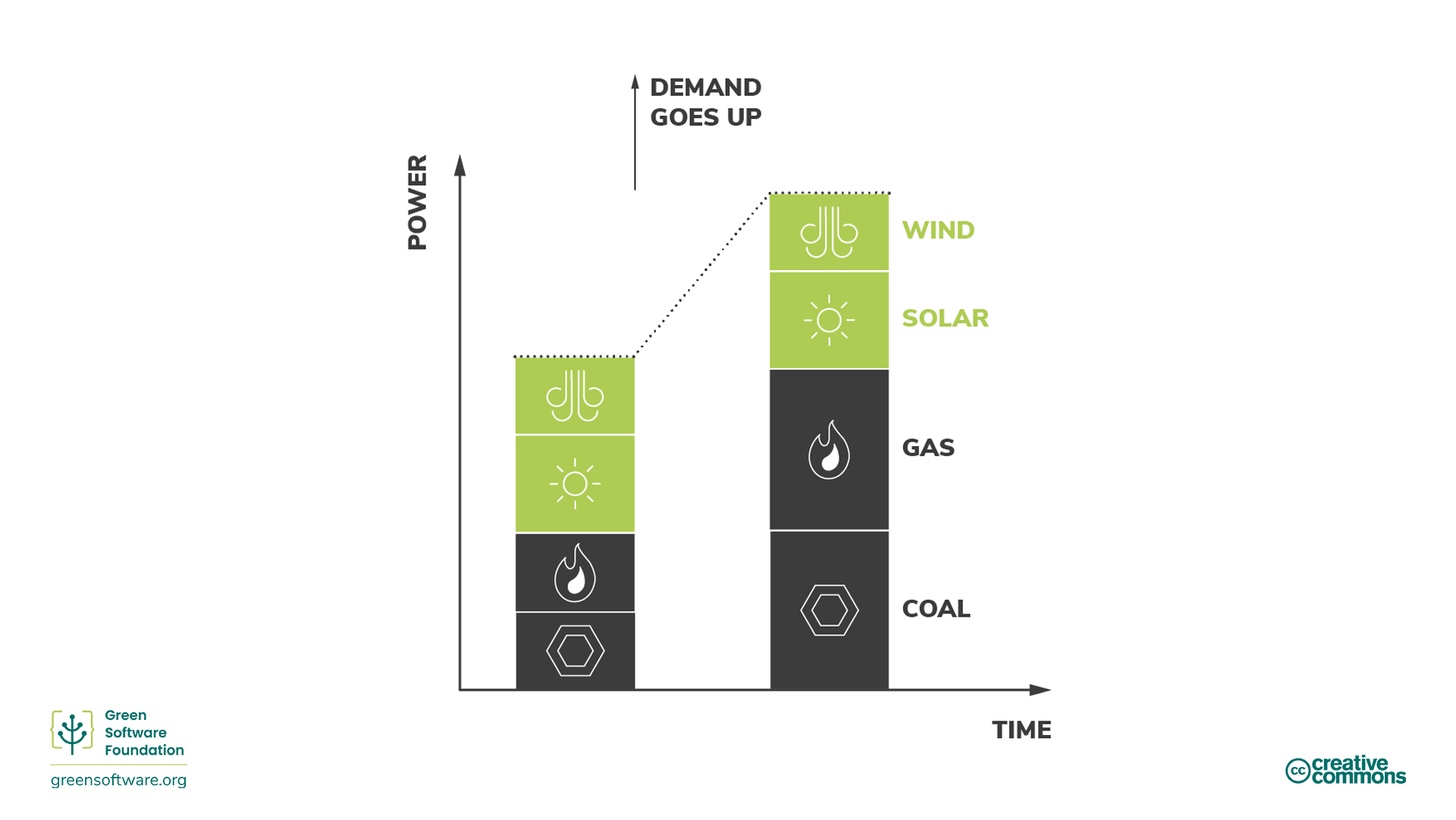

When the demand for electricity goes up, utilities need to increase the supply to balance supply and demand. They can do this in one of two ways:

- Buy more energy from renewable sources that are currently being curtailed

If you are curtailing, it means you have excess energy you could dispatch. Renewable energy is already the cheapest, so curtailed renewable energy will be the cheapest dispatchable energy source. Renewable plants will then sell the energy they would have had to curtail.

- Buy more energy from fossil fuel plants.

Fossil fuels are inherently dispatchable; they can quickly increase energy production by burning more. However, coal costs money, so this is the least preferred solution.

Energy markets are some of the most complex markets in the world so the above explanation is a simplification. But what’s important to understand is that our goal is to increase investment into lower carbon energy sources, like renewables, and decrease investment into higher carbon sources, like coal. The best way to ensure money flows in the right direction is to make sure you use electricity with the least carbon intensity.

How to be more carbon aware

Using electricity when the carbon intensity is low is the best way to ensure investment flows towards low-carbon emitting plants and away from high-carbon emitting plants.

There is a global transformation happening right now. All around the world, electricity grids are changing from primarily burning fossil fuels to sourcing energy from lower carbon sources like wind and solar. This is one of our best hopes for meeting our global reduction targets. As green users of HPC, let’s see some of the ways we can help accelerate that transition.

The primary driver for the transition is economic rather than any sustainability target. Renewables are winning because they are cheaper and getting even more affordable over time. So, to help accelerate the transition, we need to make renewable plants more profitable and fossil fuel plants less profitable. The best way to do that is to use more electricity when it’s coming from lower-carbon sources like renewables and less electricity when it’s coming from higher-carbon sources.

Carbon intensity is lower when more energy comes from lower-carbon sources and higher when it comes from higher-carbon sources.

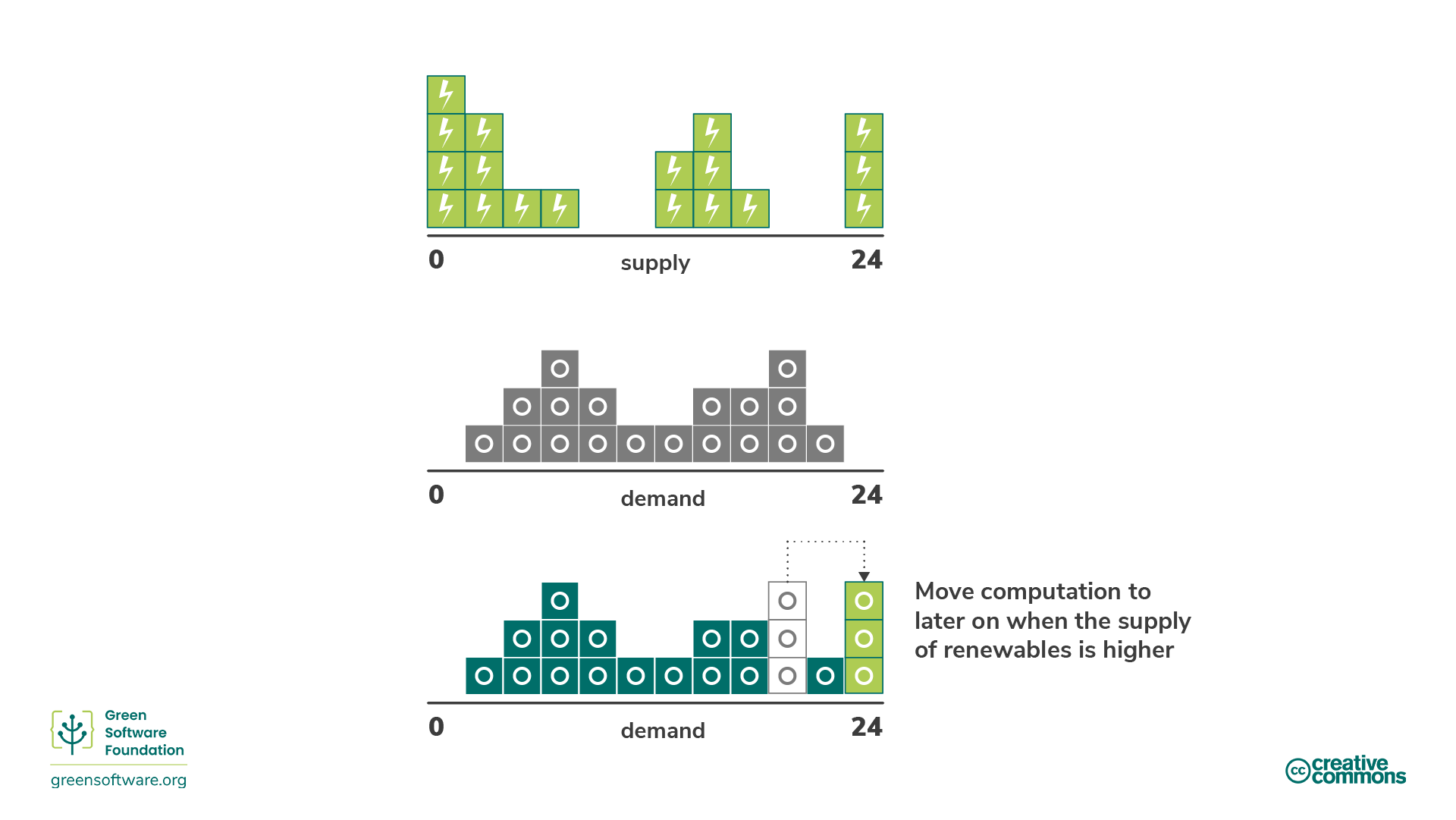

Demand shifting

Being carbon aware means responding to shifts in carbon intensity by increasing or decreasing your demand. If your work allows you to be flexible with when and where you run workloads, you can shift accordingly - consuming electricity when the carbon intensity is lower and pausing production when it is higher. For example, running a simulation or model at a different time or region with much lower carbon intensity.

Studies show these actions can result in 45% to 99% carbon reductions depending on the number of renewables powering the grid.

Demand shifting can be further broken down into spatial and temporal shifting.

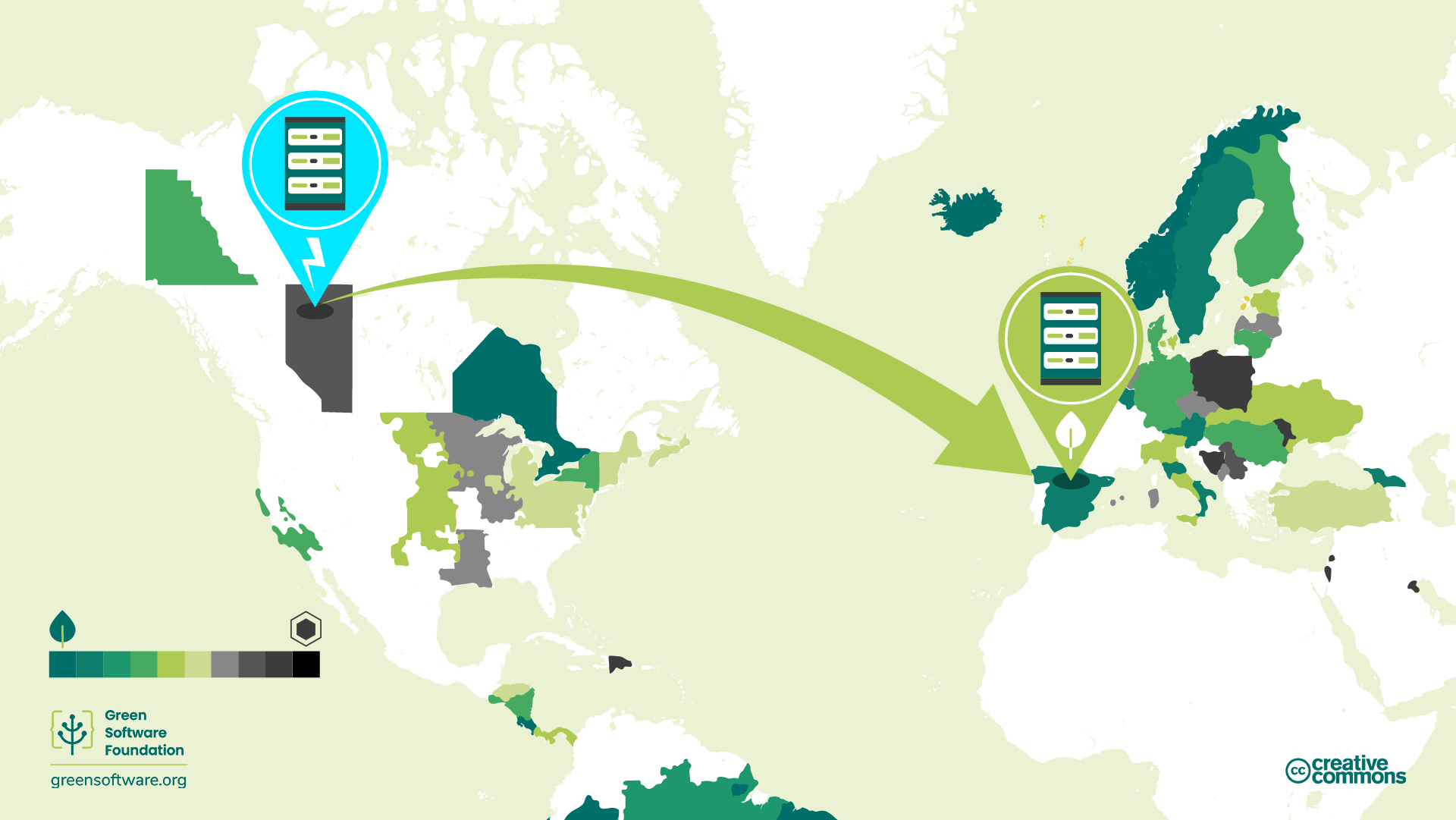

Spatial shifting

Spatial shifting means moving your computation to another physical location where the current carbon intensity is lower. It might be a region that naturally has lower carbon sources of energy. For example, using an HPC facility sited in a location that is currently windy and so has a high proportion of wind power.

This requires you to have the ability to run on different HPC resources in different locations - for example, you could chose between running on a local HPC resource or a national HPC resource located elsewhere.

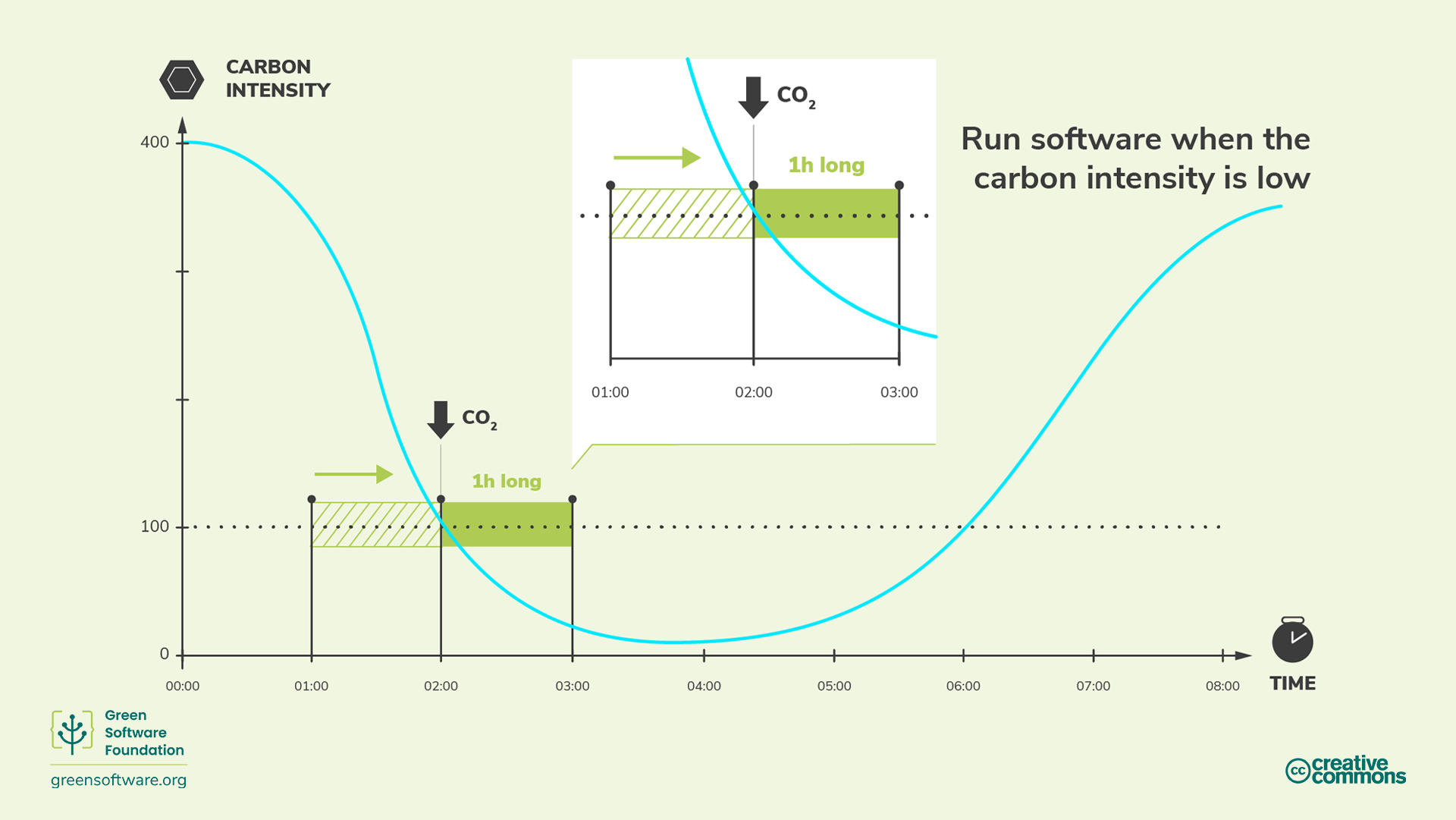

Temporal shifting

If you can’t shift your computation spatially to another region, another option you have is to shift to another time. Perhaps later in the day or night when it’s sunnier or windier and, therefore, the carbon intensity is lower. This is called temporal demand shifting. We can predict future carbon intensity reasonably well through advances in weather forecasting.

An example of a service that can predict carbon intensity to enable temporal demand shifting is the carbonintensity.org.uk website and API.

Some of the large technology companies have recognised the importance of carbon awareness and are using advanced modeling techniques to implement demand shifting.

- Google Carbon Aware Data Centers - Google launched a project to make some of the cloud workloads carbon aware. They created models to predict tomorrow’s carbon intensity and workload. They then shaped large-scale workloads so more would happen when and where the carbon intensity is lowest, but in such a way that they could still handle the expected load.

- Microsoft Carbon Aware Windows - Microsoft announced a project to make Windows 11 more sustainable. Initially, this means running Windows updates when the carbon intensity is lower.

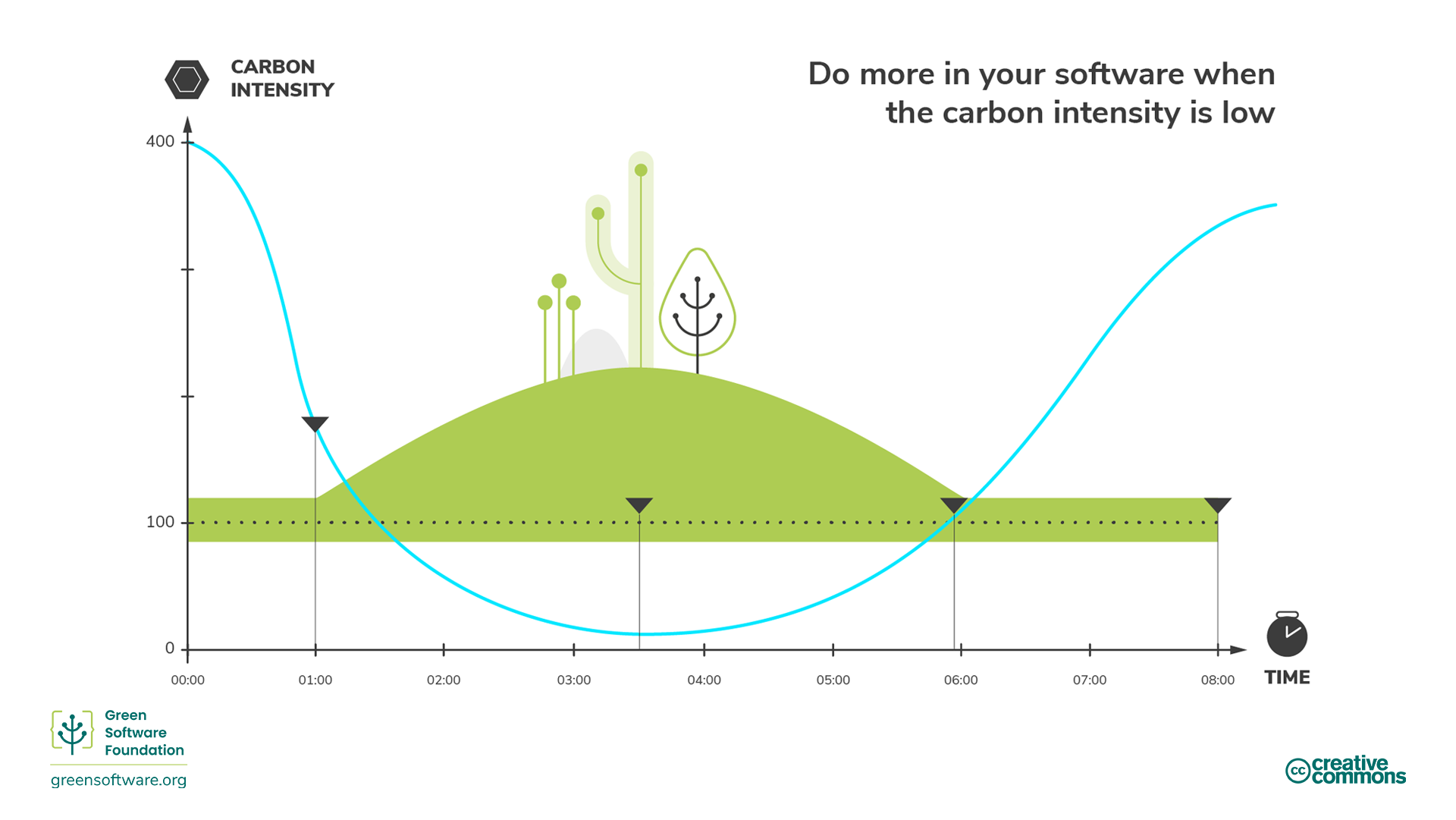

Demand shaping

Demand shifting is the strategy of moving computation to regions or times when the carbon intensity is lowest. Demand shaping is a similar strategy. However, instead of moving demand to a different region or time, we shape our computation to match the existing supply.

- If carbon intensity is low, increase the demand; do more (or faster) calculations.

- If carbon intensity is high, decrease demand; do less (or slower) calculations.

Demand shaping for carbon-aware HPC use is all about the supply of carbon. When the carbon cost of running your simulation or model becomes high, shape the demand to match the supply of carbon. This can happen automatically, or the user can make a choice.

Eco mode is an example of demand shaping. Eco modes are found in everyday appliances like cars or washing machines. When activated, some amount of performance is sacrificed in order to consume fewer resources (gas or electricity). Because there is this trade-off with performance, eco modes are always presented to a user as a choice.

Software or HPC services can also have eco modes that can - either automatically or with user consent - make decisions to reduce carbon emissions.

One example of this is video conferencing software that adjusts streaming quality automatically. Rather than streaming at the highest quality possible at all times, it reduces the video quality to prioritize audio when the bandwidth is low.

Another example is TCP/IP. The transfer speed increases in response to how much data is broadcast over the wire.

A third example is progressive enhancement with the web. The web experience improves depending on the resources and bandwidth available on the end user’s device.

Demand shaping is related to a broader concept in sustainability, which is to reduce consumption. We can achieve a lot by becoming more efficient with resources, but we also need to consume less at some point.

As green users of HPC, we would consider cancelling or reducing the power intensity of our workflow when the carbon intensity is high instead of demand shifting - reducing the energy demands of our work.

Key Points

- Carbon awareness means understanding that the energy you consume does not always have the same impact in terms of carbon intensity.

- Carbon intensity varies depending on the time and place it is consumed.

- The nature of fossil fuels and renewable energy sources means that consuming energy when carbon intensity is low increases the demand for renewable energy sources and increases the percentage of renewable energy in the supply.

- Demand shifting means moving your energy consumption to different locations or times of days where the carbon intensity is lower.

- Demand shaping means adapting your energy consumption around carbon intensity variability in order to consume more in periods of low intensity and less in periods of high intensity.

Content from Hardware Efficiency

Last updated on 2025-01-17 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 25 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is embodied carbon on HPC systems?

- How can embodied carbon efficiency be improved on HPC systems?

- What can I do to improve the embodied carbon efficiency of my use of HPC systems?

Objectives

- Understand what is meant by “embodied carbon” in the contect of HPC systems

- Learn how embodied carbon efficiency can be improved by extending the lifespan of HPC systems and improving performance of applications on HPC systems

- Appreciate that the balance between embodied and operational carbon emissions on a particular HPC system influences how we go about maximising carbon efficiency

Introduction

The hardware used that makes up the HPC systems you are using is an important element to consider when looking to be greener users of HPC.

You will see how embodied carbon is a hidden cost when it comes to hardware and the different measures you can take to reduce the impact that the creation, destruction and running of this hardware involves. For example, extending its lifetime or switching to cloud servers.

Key concepts

Embodied carbon

The device you are using to read this on produced carbon when it was manufactured and, once it reaches the end of life, disposing of it may release more. Embodied carbon (also referred to as “embedded carbon”) is the amount of carbon pollution emitted during the creation and disposal of a device.

When calculating the total carbon pollution for HPC services, both the carbon pollution associated with running the system as well as the embodied carbon of the system must be accounted for.

Embodied carbon varies significantly between end-user devices. For some devices, the carbon emitted during manufacturing is much higher than that emitted during usage, as illustrated by a study from University of Zurich. As a result, the embodied carbon cost can sometimes be much higher than the carbon cost of the electricity powering it.

By thinking in terms of embodied carbon, any device, even one not consuming electricity, is responsible for the release of carbon over its lifetime.

Amortisation

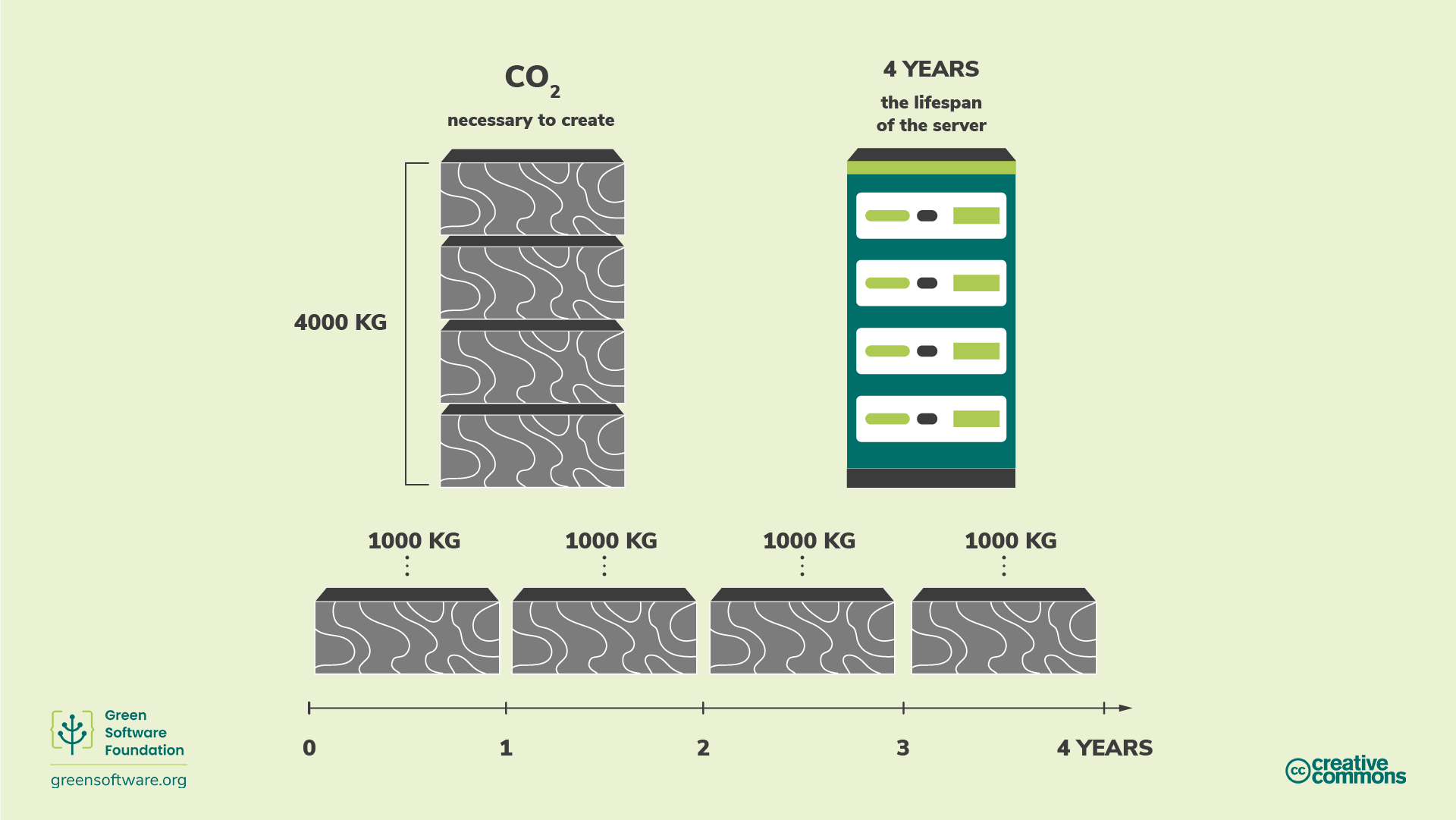

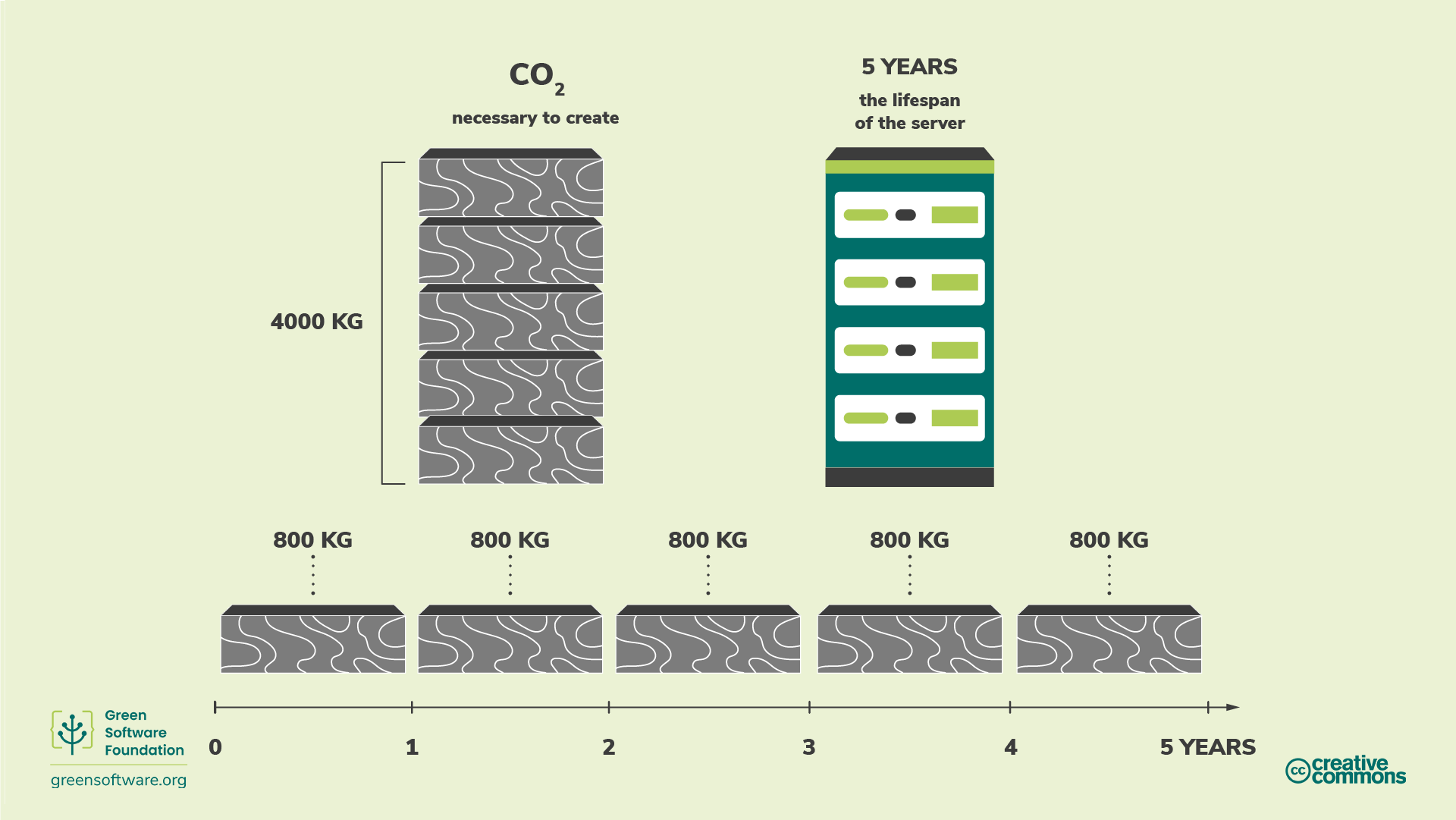

A way to account for embodied carbon is to amortise the carbon over the expected life span of a device. For example, suppose it took 4000 kgCO2e to build an HPC system, and we expect it to last four years. Amortisation means that we can say the HPC system emits 1000 kgCO2e/year.

How to improve hardware efficiency

If we take into account the embodied carbon, it is clear that by the time we come to install an HPC system, it’s already emitted a good deal of carbon. Computers also have a limited lifespan, which means they eventually are unable to handle modern workloads and need to be replaced. In these terms, hardware is a proxy for carbon, and since our goal is to be carbon efficient, we must also be hardware efficient.

There are two main approaches to hardware efficiency:

- Extending the lifespan of the hardware - which reduces the carbon emisison rate per unit of time due to amortisation

- Increasing the utilisation and performance of the hardware - getting more useful work out of the hardware per unit of time

Extending the lifespan of hardware

In the example we saw previously, if we can add just one more year to the lifespan of our HPC system, then the amortised carbon emissions rate drops from 1000 kgCO2e/year to 800 kgCO2e/year.

HPC systems have historically had lifetimes of around 5-7 years at which point they are replaced by newer systems that provide improved performance and functionality and that are typically more energy efficient. However, extending the lifetime of HPC systems for longer periods may lead to improved carbon efficiency and using older HPC systems for our research may lead to more carbon efficient use of HPC.

Carbon efficiency can be complex - flexibility is key

Understanding what is the most carbon efficient way to make use of HPC systems (and the most carbon efficient way to operate then, including choosing their lifetime) can be complex as it depends on many factors: the embodied carbon of the hardware, the lifetime, the carbon intensity of the electricity supply and how that changes over the service lifetime, how efficiently the workload you are running runs on the type of hardware provided by the system. However, one key aspect of being able to use HPC in a carbon efficient way is for your workflow to have the flexibility to run on different system types in an efficient manner.

Increasing utilisation and performance

As well as increasing the lifespan to improve the embodied carbon efficiency, we can also get more out of the HPC hardware while we have it.

At a service/system level this often corresponds to maximising the usage of the service - it’s better to have 100% utilisation than 20% utilisation because of the cost of embodied carbon (and also because of the fact that even idle components in HPC systems consume some electricity).

For individual users and groups on HPC systems, improving the carbon efficiency with respect to embodied carbon typically corresponds to increasing the performance of their use of the system so you get more output per unit of time. Of course, increasing the performance of your use may lead to higher power draw and higher electricity use increasing the emissions from the use of electricity. This means that you need to know what the balance between embodied emissions and emissions from electricity use are for the HPC system you are using to make useful choices about improving your carbon efficiency. There are three potential scenarios:

- Embodied carbon dominates: run as high performance as possible irrespective of electricity use to maximise carbon efficiency

- Embodied carbon and carbon from electricity use are evenly balanced: you need to find a balance of performance and energy efficiency to maximise carbon efficiency

- Carbon from electricity use dominates: run in as energy efficient manner as possible to maximise carbon efficiency

Key Points

- Embodied carbon is the amount of carbon pollution emitted during the creation and disposal of an HPC system.

- When calculating your total carbon pollution, you must consider both that which is emitted when running the on the HPC system as well as the embodied carbon associated with its creation and disposal.

- Extending the lifetime of an HPC system has the effect of amortising the carbon emitted so that its embodied CO2e/year is reduced.

- Increasing utilisation and performance also improve the embodied carbon efficiency from HPC system use.

- You need to know what the balance between embodied carbon and operational carbon is on the HPC systems you are using to be able to decide how to maximise your carbon efficiency.

Content from Measurement

Last updated on 2025-03-07 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How are emissions measured and classified under the GHG protocol?

- How do I use the GHG protocol to estimate emissions from my use of HPC?

Objectives

- Understand how emissions are classified in the widely-used GHG protocol

- Know which GHG protocol classifications are relevant to use of HPC systems

- Learn a methodology to use GHG protocol to estimate the emissions associated with our use of HPC systems

- Understand how emission rates from HPC can be calculated

Introduction

The Greenhouse Gas (GHG) protocol is the most commonly-used method for organisations to measure their total carbon emissions. Understanding GHG scopes and how to measure your software against industry standards will help you see to what extent you are reducing carbon emissions and how that fits with wider activities to reduce emissions.

To complement the GHG protocol, and if yo develop software that is used by others, you can also use the Software Carbon Intensity (SCI) specification. While the GHG is a more generic measurement suitable for all types of organisations, the SCI is specifically for measuring a rate of software emissions and designed to incentivise the elimination of those emissions.

The GHG protocol

The Greenhouse Gas protocol is the most widely used and internationally recognized greenhouse gas accounting standard. 92% of Fortune 500 companies use the GHG protocol when calculating and disclosing their carbon emissions and it provides the basis of emissions reporting for most countries (including the UK). Using the GHG protocol allows us to compare our emissions from use of HPC systems to other sources of emissions in a quantitative way.

The GHG protocol divides emissions into three scopes:

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from operations owned or controlled by the reporting organisation, such as on-site fuel combustion or fleet vehicles.

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions related to emission generation of purchased energy, such as heat and electricity.

-

Scope 3: Other indirect emissions from all the

other activities you are engaged in. Scope 3 emissions are typically

split into two further categories: Upstream Emissions and

Downstream Emissions:

- Upstream Scope 3 Emissions: Includes all emissions from an organisation’s supply chain, e.g. emissions from manufacturing and shipping a product

- Downstream Scope 3 Emissions: Emissions resulting from the use of a product, e.g. the electricity customers may consume when using your product or waste output from the product

Scope 3, sometimes referred to as value chain emissions, is the most significant source of emissions and the most complex to calculate for many organisations. These encompass the full range of activities needed to create a product or service, from conception to distribution. In the case of a laptop, for example, every raw material used in its production emits carbon when being extracted and processed (part of the upstream scope 3 emissions). Value chain emissions also include emissions from the use of the laptop, meaning the emissions from the energy used to power the laptop after it has been sold to a customer (part of downstream scope 3 emissions).

Through this approach, it’s possible to sum up all the GHG emissions from every organization and person in the world and reach a global total.

What scope does my application fall into?

We have already seen how the GHG protocol asks us to bucket emissions from HPC system use according to scopes 1-3. But how do we actually do this?

Exercise: What scope for HPC emissions?

Throughout this course we have spoken about emissions from two different sources associated with our use of HPC: emissions from the electricity used to run our models/simulations on HPC systems and embodied emissions from the HPC system hardware. Given the definitions of scope 1-3 emissions given above, what scope do you think these two different sources of HPC system use emissions fall into?

- Emissions from electricity used: these would be classified as Scope 2 emissions

- Embodied emissions from HPC system hardware: these would be classified as Upstream Scope 3 emissions

HPC electricity: Scope 2 or Downstream Scope 3?

Whether the emissions from electricity use on HPC systems are Downstream Scope 3 or Scope 2 really depends on who is computing the emissions and for what purpose. From the viewpoint of the hardware vendor who sells and manufactures the HPC system, the electricity use falls into Downstream Scope 3 emissions but for operators and users of the HPC system they would classified as Scope 2 emissions. As we are approaching this subject as users of HPC systems we will always classify the emissions from our electricity use on HPC systems as Scope 2.

In short, Downstream Scope 3 emissions are not usually relevant for use of HPC systems as this part of the emissions is reported in the Scope 2 emissions.

How to calculate your HPC emissions

Quantifying the emissions from your work (and generating an emissions

rate, as described below) are critical steps on the path to reducing and

potentially eliminating emissions from your use of HPC systems. The

formula for calculating your emissions from use of HPC systems

(HPC-E) is straightforward:

HPC-E = (E * I) + M-

E= Energy consumed by HPC use (in kWh) -

I= Location-based marginal carbon intensity (in kgCO2/kWh) -

M= Embodied emissions

You can calculate this on a per job basis or for a larger grouping of HPC use - even for a full lifetime of an HPC service.

Instead of bucketing the carbon emissions of HPC use into scopes 1-3,

it buckets them into operational emissions (carbon

emissions from the electricity required for your HPC use, represented by

E * I) and embodied emissions (carbon

emissions from the physical HPC system components, represented by

M).

Follow these steps to calculate your HPC emissions.

- Gather your energy use - this can be measured or estimated and is often a combination of measured and estimated data

- Determine the carbon intensity at the location of the HPC system you are using

- Determine the embodied emissions associated with your use of HPC

- Compute your total HPC emissions

1. Gather energy use

Many HPC systems now provide energy use data for jobs run on the system. If this is the case, you can use these as the starting point for calculating your energy use of HPC resources. If this is not available, then you may need to estimate the energy use of your use of resources from component power draw. Even if you have energy use data available this may only cover energy use of compute nodes (or even processors on compute nodes) so you do typically have to do some estimation of power draw of other components to know how much extra energy to add on to include them in your calculation.

If you are really lucky, the HPC system staff will have done this calculation for you. As has been done for the UK National Supercomputing Service, ARCHER2: Estimating emissions from ARCHER2

We will cover two different ways to estimate the power draw of HPC systems which can then be used to compute energy use.

- Use the total power draw of the system

- Use the per-component power draw of the system

Heterogeneous systems

The methodologies outlined below all assume the compute nodes are heterogeneous. What do you do if this is not the case and some nodes on the system have GPU and others do not, for example? In this case, you should try, as much as possible, to treat each homogeneous partition as its own smaller HPC system to help calculate energy use.

a. Using total power draw

One of the simplest ways to estimate your energy use is to use the

total power draw of the HPC system and divide it by the number of

components to get a mean power draw per component that can be used to

estimate energy use. For example, if the total power draw of the system

is 250 kW and it contains 512 GPU, then the mean power draw per GPU is

250 kW / 512 GPU = 0.488 kW/GPU. This, in turn, means the

energy used for 12 hours use of 2 GPU is

12 hours * 2 GPU * 0.488 kW/GPU = 11.7 kWh.

You should use the component that you measure resource use in to compute the mean power draw. For example. if your usage is measured in GPUh, then compute the power draw per GPU; if your usage is measured in nodeh, compute the power draw per node.

b. Using per-component power draws

This approach requires more detailed information being available on the power draw of different components though measurement or from information from the vendors of the components. If you are getting your energy use from counters on the compute nodes (as is sometimes possible on HPC systems) then this approach allows you to estimate additional energy overheads that need to be added on in addition to the measured power draw.

We illustrate this approach using the estimates for the ARCHER2 HPC system:

| Component | Count | Loaded power draw per unit (kW) | Loaded power draw (kW) | % Total | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compute nodes | 5,860 nodes | 0.41 | 2,400 | 85% | Measured by on system counters |

| Interconnect switches | 768 switches | 0.24 | 240 | 9% | Measured by on system counters |

| Lustre storage | 5 file systems | 8 | 40 | 1% | Estimate from vendor |

| NFS storage | 4 file systems | 8 | 32 | 1% | Estimate from vendor |

| Coolant distribution units | 6 CDU | 16 | 96 | 3% | Estimate from vendor |

| Total | 2,808 | 99% |

In this case, we have a mix of data measured on the system (power

draw of the compute nodes and power draw of the interconnect switches)

and estimates from the vendor (storage systems and CDU). Here, the total

power draw is estimated at 2,808 kW, there are 5,860 compute nodes and

the unit of resource is nodeh so we can calculate the mean per node

power draw (including all the components in the table) in the same way

as we did for method (a) with

2,808 kW / 5,860 nodes = 0.480 kW/node and use this to

compute energy consumption based on how many nodeh we use.

However, on ARCHER2 we also have the total compute node energy use available per job to users from the Slurm scheduler. The table above shows that the compute nodes contribute around 85% of the total power draw of ARCHER2 (of the components included) so an alternative method to compute the energy use is to use the measurement from the scheduler and add an additional 15% to cover the energy used by other components. This is, in fact, the methodology used for computing per job energy use on ARCHER2.

Add in energy from plant overheads

As well as the energy used by the system itself, there is also the energy used by the plant that supplies power and cooling to the HPC system. Different data centres have different sizes of overheads and this is given by PUE (Power Use Efficiency). For example, a PUE of 1.25 indicates that an additional 25% energy use is added on top of the system energy use to account for the plant.

The PUE will vary with outside weather conditions at the data centre. For the ARCHER2 example, PUE is typically less than 10% so, s a conservative estimate, they add an additional 10% energy use to the total to account for plant overheads.

So, for the ARCHER2 example, the process for computing your total energy use becomes:

- Measure total energy use from all jobs run

- Add 15% extra energy to cover energy use from other components

- Add another 10% energy use top of this new total to cover plant overheads

2. Determine local carbon intensity

Once you have your energy use then you need to convert this to emissions using the carbon intensity for the electricity supply for the HPC system. In most cases, HPC systems are powered by the energy grid and many energy grids provide details on the carbon intensity as a function of time.

For the UK, the carbon intensity is dependent on location and time. You can access the values through different web services but one that is commonly used is the Carbon Intensity API. Carbon intensity is reported for every region every 30 minute interval. To estimate your emissions you can either use the fine grained intensity matched to the run times of your HPC system use or use an aggregate value over a longer period. The aggregate value is a simpler choice for a first estimate. The table below shows the mean carbon intensities for the different regions of the UK national grid for 2024 ordered from lowest to highest.

| Region | Mean 2024 CI (gCOe/kWh) |

|---|---|

| NE England | 22 |

| S Scotland | 26 |

| N Scotland | 30 |

| NW England | 48 |

| N Wales | 77 |

| E England | 108 |

| London | 125 |

| W Midlands | 125 |

| SE England | 135 |

| Yorkshire | 135 |

| S England | 186 |

| E Midlands | 203 |

| SW England | 242 |

| S Wales | 255 |

For the UK, where you place your HPC system can have a tenfold impact on emissions from energy use.

3. Determine embodied emissions

Upstream Scope 3 emissions

Remember that we are considering only upstream Scope3 emissions here. The emissions from electricity use are captured in the Scope 2 emissions estimates.

Calculating the embodied emissions can be more difficult than the operational emissions from energy consumption as it can be more difficult to get information on embodied emissions from hardware. You may, of course, be lucky and the HPC system you are using could already provide estimates of the embodied emissions which you can use.

If you need to estimate this yourself, the major contributors to embodied emissions are likely to be:

- Compute nodes

- Interconnect switches

- Storage

so these are the best place to start. Bear in mind that each HPC system is different so other components may need to be taken into account. As a rule of thumb, you should look at the HPC system to see which components there are lots of and use that as the starting place. Complex components (such as nodes, storage and switches) are likely to have much higher embodied emissions than simpler components (pumps, fans, cables etc.).

As an example, here is how we have estimated embodied emissions for ARCHER2:

| Component | Count | Estimated kgCO2e per unit | Estimated kgCO2e | % Total Scope 3 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compute nodes | 5,860 nodes | 1,100 | 6,400,000 | 84% | (1) |

| Interconnect switches | 768 switches | 280 | 150,000 | 2% | (2) |

| Lustre HDD | 19,759,200 GB | 0.02 | 400,000 | 6% | (3) |

| Lustre SSD | 1,900,800 GB | 0.16 | 300,000 | 4% | (3) |

| NFS HDD | 3,240,000 GB | 0.02 | 70,000 | 1% | (3) |

| Total | 7,320,000 | 100% |

References:

- IRISCAST Final Report

- Estimate taken from IBM z16™ multi frame 24-port Ethernet Switch Product Carbon Footprint

- Tannu and Nair, 2023

Note that there is a large amount of uncertainty for Scope 3 emissions due to lack of high quality embodied emissions data. The number used for the compute node emissions is at the high end of estimated values for a CPU-only compute node and the actual value could be as much as 15% lower at around 900 kgCO2e/node. If the lower value is used, it reduces the overall estimated embodied emissions but does not significantly change the fraction of emissions attributed to the compute nodes.

Other embodied emissions sources

We have not included embodied emissions associated with the data centre buildings and plant in the analysis above. The IRISCAST report mentioned above provides an evaluation of these values. While the total embodied emissions can be high for these items, their long lifespan means that their contribution to the embodied emissions during the lifespan of a particular HPC system are generally much less significant than the embodied emissions from the HPC system hardware itself.

4. Compute your total HPC emissions

Now we should have all the data we need to compute our total emissions from HPC system use:

-

E- Total energy used -

I- Carbon intensity -

M- Embodied emissions estimate

Remember the equation for computing total emissions from HPC system

use (HPC-E):

HPC-E = (E * I) + Mwe can plug the numbers in and come up with a value for the total emissions arising from our use of HPC.

E * I on a per job basis

Rather than computing total energy use and then using an aggregate

value for the carbon intensity, it may make more sense to compute

E * I on a per-job basis using the carbon intensity value

at the job time.

HPC Carbon Intensity (HPC-CI) specification

We now describe a methodology (the HPC Carbon Intensity specification, HPC-CI) to calculate your emissions from HPC system use and to encourage action towards eliminating emissions.

It is not a replacement for the GHG protocol, but an additional metric that helps you understand how your HPC system use can be measured in terms of carbon emissions so they can make more informed decisions. While the GHG protocol calculates the total emissions, the HPC-CI is about calculating the rate of emissions. In automotive terms, HPC-CI is more like a miles per gallon measurement and the GHG protocol is more like the total carbon footprint of a car manufacturer and all their cars they produce every year.

An important thing to note is that it is not possible to reduce your HPC-CI rate by purchasing offsets in the form of neutralisations, compensations, or by offsetting electricity in the form of renewable energy credits (we will cover this in more detail in the next section of the workshop). This means that HPC services or use that makes no effort toward reducing its emissions but spends money on carbon credits cannot reduce their HPC-CI rate.

Offsets are an essential component of any climate strategy; however, offsets are not eliminations and therefore are not included in the HPC-CI metric.

If you make your HPC use more energy efficient, hardware efficient, or carbon aware, your HPC-CI rate will decrease. The only way to reduce your rate is to invest time or resources into one of those three principles. As such, adopting the HPC-CI metric for your HPC use, will drive investment into one of the three pillars of green HPC use.

The HPC-CI equation

The equation to calculate an HPC-CI rate is simple and very closely related to the calculation of total emissions presented above:

HPC-CI = [(E * I) + M] per R-

E= Energy consumed by HPC use (in kWh) -

I= Location-based marginal carbon intensity (in kgCO2/kWh) -

M= Embodied emissions -

R= Functional unit (e.g. iterations, simulated time, calculation cycles, research papers published, cost)

This yields an emissions rate in carbon emissions per functional unit

(HPC-E per R), e.g. kgCO2e/iteration.

The steps to calculate your HPC-CI score are the similar as calculating your emissions described above with additional steps to produce the rate. Steps 1-4 are identical the methodology described above:

- Gather your energy use

- Determine the carbon intensity at the location of the HPC system you are using

- Determine the embodied emissions associated with your use of HPC

- Compute your total HPC emissions

- Select your functional unit (

R) - Calculate your HPC-CI rate

Estimating emissions associated with future use of HPC systems

How can the HPC-CI rate be reduced?

Depends a bit on whether the operational emissions or embodied emissions dominate

-

Operational emissions dominate:

- Improve the energy efficiency of your use (e.g. power caps, different algorithms)

- Temporal shifting - run when carbon intensity is lower

- Spatial shifting - run on system where carbon intensity is lower, run on hardware which has better energy efficiency for your use case (e.g. GPU may be more energy efficient for your use)

-

Embodied emissions dominate:

- Make your use more performant - more output per unit of time (even at the expense of energy efficiency)

- Extend the lifetime of the HPC system (reduced emissions due to longer amortisation)

- Spatial shifting - run on system which has lower embodied emissions rate for your use

Key Points

- The GHG protocol is a metric for measuring an organisation’s total carbon emissions and is used by organisations all over the world.

- The GHG protocol puts carbon emissions into three scopes. Scope 3, also known as value chain emissions, refers to the emissions from organisations that supply others in a chain. In this way, one organisation’s scope 1 and 2 will sum up into another organization’s scope 3.

- You can use the GHG protocol to estimate your emissions from HPC system use but it requires access to good quality information from the HPC systems you are using.

- The HPC-CI is a metric designed specifically to calculate emissions from HPC systems and is a rate rather than a total. This can be used to measure improvements in emissions efficiency and drive reductions in emissions.

Content from Climate Commitments

Last updated on 2025-02-28 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What methodologies are available to reduce carbon emissions and how do they differ?

- What is the difference between “net zero” and “carbon neutral” climate commitments?

- How can organisations match renewable energy availability to demand?

Objectives

- Understand different carbon reduction methodologies and their role in meeting climate commitments.

- Appreciate the difference between “net zero” and “carbon neutral” climate commitments.

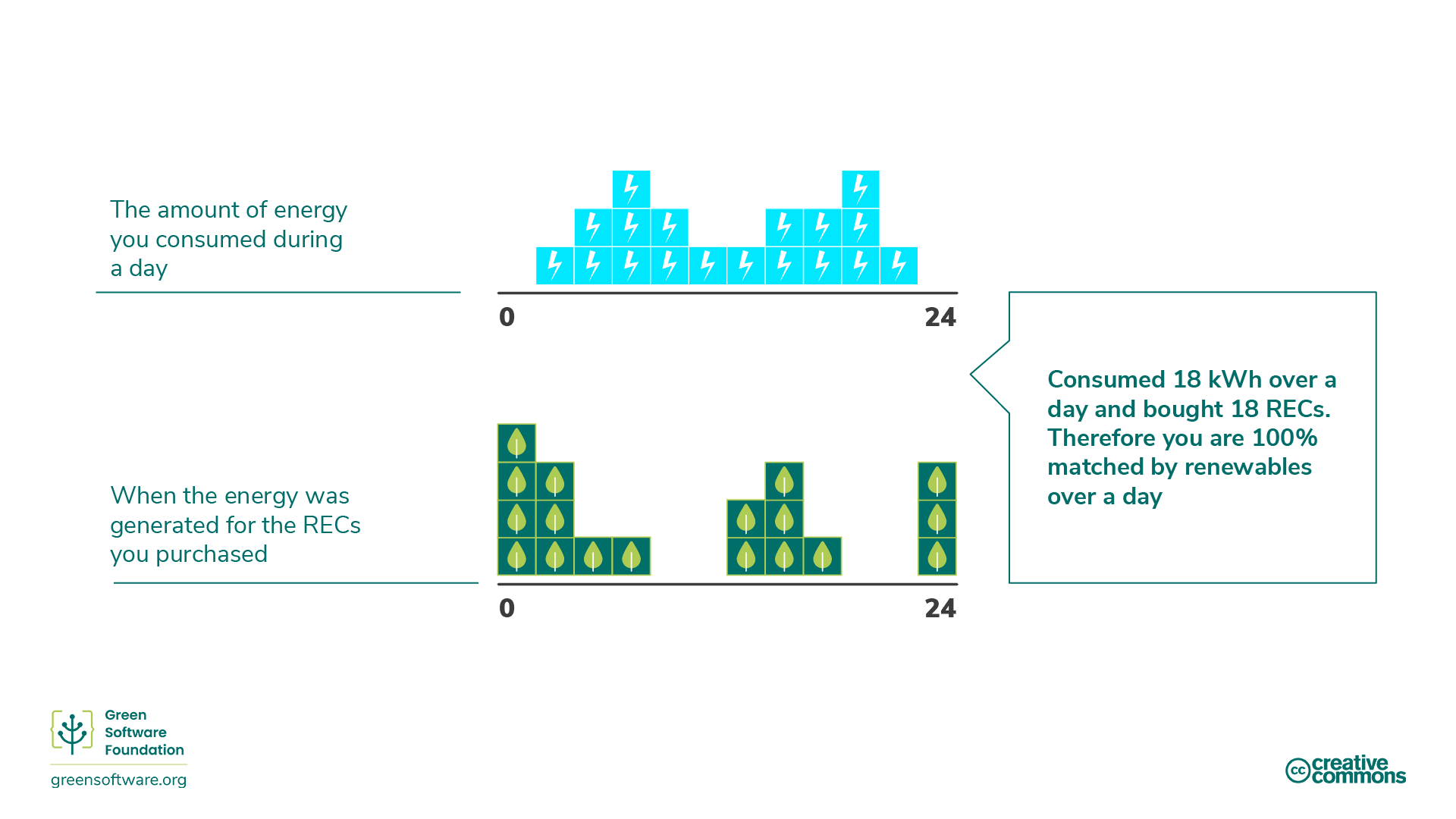

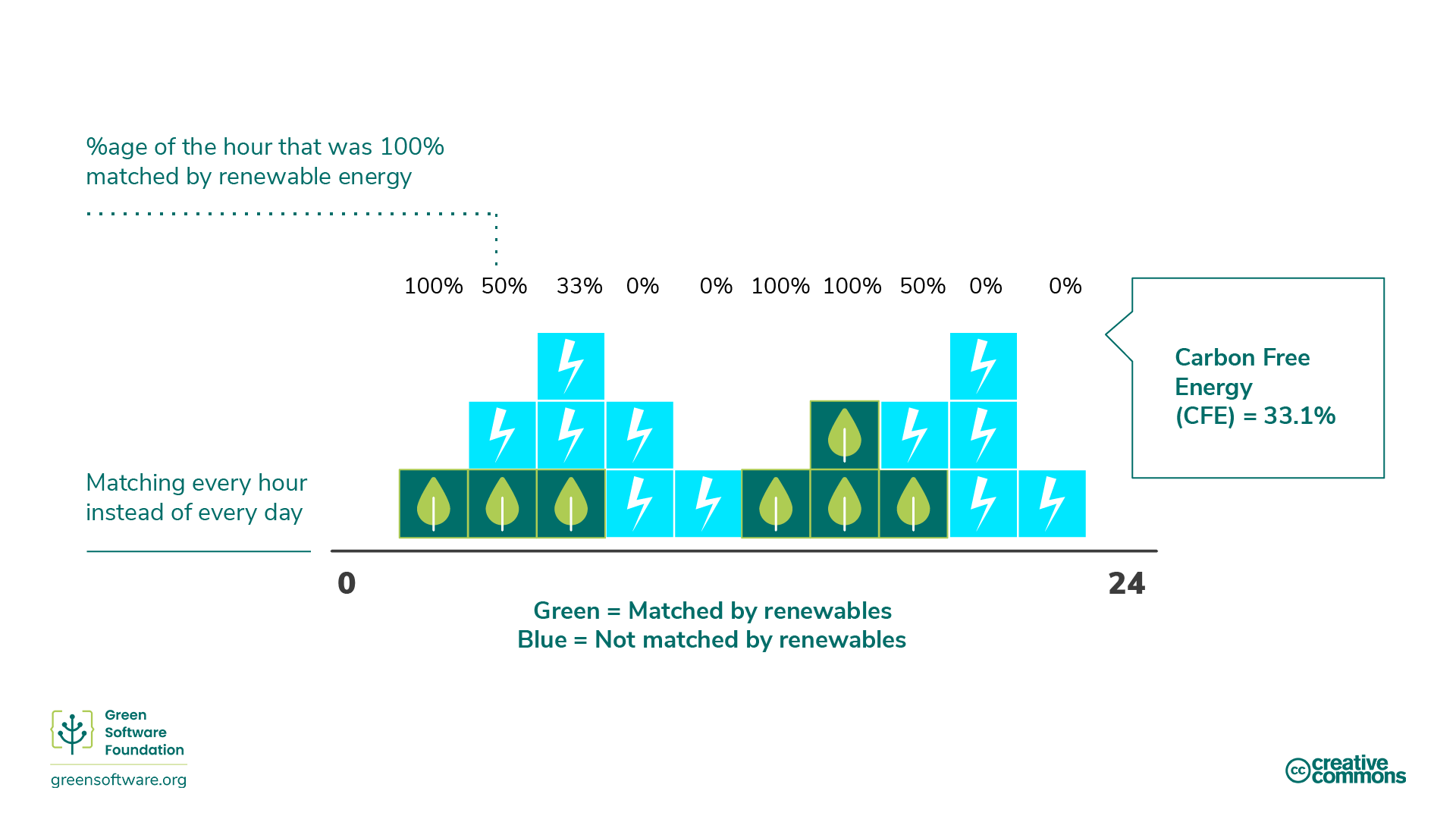

- Understand matching strategies for energy from renewable sources.

Introduction

In recent years, many economic actors have sought to reach different climate goals by making various commitments.

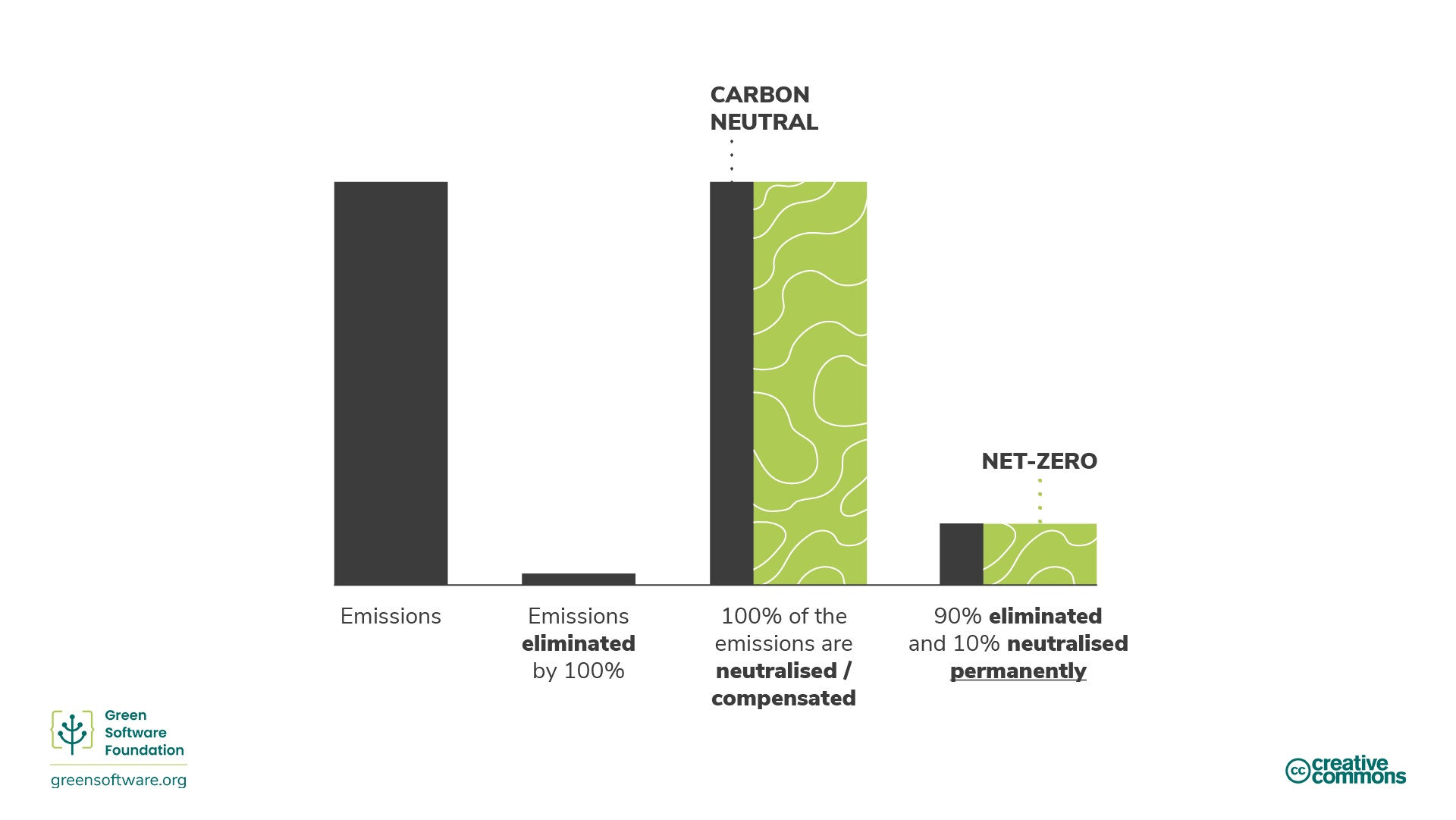

The terms “net zero”, “carbon neutral”, “carbon negative” and “climate neutral” have been used interchangeably with the primary objective to remove, reduce and prevent carbon emissions. As interest in these targets grows, it is essential to have a common understanding of what they mean and how to achieve them through the strategies and measurement procedures we have learnt.

Carbon reduction methodologies

There are many ways to reduce emissions but it’s important to understand the exact mechanism of the reduction when thinking about reduction targets.

Abatement / Carbon Elimination

The Science Based Targets Initiative refers to a mechanism called abatement, which means eliminating sources of CO2 emissions associated with an organisation’s operations and value chain so that they do not enter the atmosphere. The value chain describes the full range of activities needed to create a product or service, from conception to distribution. This includes increasing energy efficiency to eliminate some of the emissions associated with energy generation.

Abatement is not enough on its own as there will always be some emissions that can’t be eliminated due to technological or economic constraints, but it must form the core of every organisation’s strategy as it is an area where almost every organisation can improve.

To balance those residual emissions, we need to look at other mechanisms such as offsets, compensations or neutralisations.

Offsets

Offsets are direct investments in emission-reduction projects through the purchase of carbon credits on the voluntary carbon market (VCM). The VCM is a decentralised market where private actors voluntarily buy and sell carbon credits that represent certified removals or reductions of GHGs from the atmosphere.

To offset emissions, you need to purchase the equivalent volume of carbon credits to compensate for those emitted, where 1 carbon credit corresponds to 1 tonne of CO2 absorbed or reduced.

Various positive benefits can stem from these projects, from ecosystem protection to empowering local communities. However, to ensure these programs are implemented correctly and have the desired effect on the environment and the aim to reach world net zero, there are global standards that they must meet such as Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and Gold Standard (GS).

SCI and Offsets

There are some limitations to carbon offsets and that is why they are not considered in an SCI score. For example, imagine two applications, both running on a HPC service that is 100% carbon offset and matched 100% by renewable energy. Application A has invested significant time and resources into making sure it is using resources efficiently, whereas application B uses resources very inefficiently. For the SCI to be a helpful metric, application A needs to score better than application B.

If the SCI considered offsets, both applications would score 0. This wouldn’t tell us anything about how efficiently they are using resources. Although application B is emitting more carbon molecules into the atmosphere per unit of output, since its score is 0 and the lowest score is 0, why would it make further investments into improving its carbon efficiency?

HPC services and users need to have plans for how to both eliminate as well as neutralise emissions and the SCI helps them to drive the elimination of emissions due to software running on HPC services. This makes the SCI an useful component to help a research project or HPC service reach net zero.

Compensating / Carbon Avoidance

Compensations are actions that organisations or individuals can take to help society avoid or reduce emissions. This is essentially investing in other organisations’ abatement projects.

This includes actions such as:

- Conservation - Credits are created based on carbon not released through protecting old trees.

- Community Projects - These projects help communities worldwide, mainly undeveloped ones, by introducing sustainable living methods.

- Waste to energy - These projects capture methane/landfill gas in smaller villages, human or agriculture waste, and convert it into electricity.

Neutralising / Carbon Removal

Neutralisations are actions that organisations or individuals take to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Neutralisations refer to the removal and permanent storage of atmospheric carbon to counterbalance the effect of releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. This includes actions such as: