Linaro Forge on ARCHER2

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

What other debugging and profiling tools are available on ARCHER2?

How can I debug and profile using a GUI?

How can I use these tools remotely?

Objectives

Understand how to prepare Linaro Forge on ARCHER2.

Know how to connect remotely using the client.

Know how to submit debugging and profiling jobs and view the results.

Aside from the tools provided by HPE Cray, the ARCHER2 CSE service has also installed Linaro Forge. You may already be familiar with these tools under the names of their previous owners, Arm and Allinea. Forge is made up of two powerful tools to help with your software development: DDT, for parallel debugging, and MAP, for parallel profiling. Both provide a GUI; the best way to use this is to run Forge as a client on your own machine and connect it to ARCHER2.

Preparing your Forge setup

Forge requires a bit of one-time setup before you can use it on ARCHER2. Thankfully a script automates the process for us. This setup is needed so that Forge knows how to interact with the Slurm installation on ARCHER2 and that it should use work as opposed to home during jobs.

We will firstly load the Forge module and then move to the work directory:

module load arm/forge

cd /work/ta000/ta000/auser

Sourcing a script in the Forge directories will do most of the setup for us:

source ${FORGE_DIR}/config-init

Warning: failed to read system config.

The clean configuration has been saved as: /work/ta000/ta000/auser/.allinea/system.config

To use this configuration file as a template for all Arm Forge users copy it to: /mnt/lustre/a2fs-work1/work/y07/shared/utils/core/arm/forge/22.1.3/system.config

The warning can safely be ignored. What’s important is that the clean system configuration is generated and stored within your work directories.

You can see that a new hidden directory has been created in your work directory, .allinea. Inside are two files, system.config and user.config that contain the actual configuration. These have been prepared for you.

At this point the one-time setup is complete.

Setting up and configuring the Linaro Forge client

Firstly, you will need to download and install the Forge software from Linaro. A client for your OS and CPU architecture should be available – you will generally want to download the client version which matches the version installed on ARCHER2. At the moment, that means version 22.1.3.

The client connects to ARCHER2 over SSH. That means that whatever we need to log in in the terminal, we will also need to provide to Forge. This has the potential to get tricky around the SSH key. A fairly failsafe way to do this

Start the client on your machine. Then, let’s configure the connection to ARCHER2. You should see a drop-down box labelled ‘Remote Launch’. Click on the box and then on ‘Configure.’

A new window will appear listing your current connections. Unless you’ve used Forge previously, this will be empty. Then click on ‘Add’ to create a new remote connection. You will need to enter the following information:

- A connection name: something sensible like

archer2ta000should help you to identify it. - The host name: provide with your username just as when you log in with SSH,

username@login.archer2.ac.uk. - Remote installation directory: copy the path

/work/y07/shared/utils/core/arm/forge/latest - Remote script: this is almost like a

.bashrcto be used by Forge. Copy and paste this path:/work/y07/shared/utils/core/arm/forge/latest/remote-init - Private key: enter the path to the SSH private key you use to connect.

- Keep-alive packets: tick the box and set to 30 seconds.

SSH key

If you are able to use the SSH Agent to provide your private key, you may not need to enter it in Forge. Just run

ssh-add <path-to-private-key>as normal in your terminal, or check if it’s already being provided withssh-add -L, then try to connect in Forge.

Click on OK, then close the connection configuration window. You should now be ready to connect to ARCHER2.

To give it a go, click on the ‘Remote Launch’ drop-down box again, then click on your new connection. If all goes well, the connection will start, the initial key exchange will succeed, and you will be prompted for your ARCHER2 TOTP in a window that briefly opens. Once you are connected, you should see that licence information is now visible at the bottom left of the Forge window, and your connection is listed at the bottom right.

Debugging with DDT

We will firstly attempt to run a debugging job using the Forge tool DDT. Let’s try to use the same code we did earlier, downloading it to a new directory in work:

wget https://epcced.github.io/archer2-intro-develop/files/gdb4hpc_exercise.c

Just as before, we need to compile the code using the -g flag to add debugging symbols. Remember, you will need to use this flag for any code you want to debug.

cc -g gdb4hpc_exercise.c -o gdb_exercise

With the code compiled, we now need to return to Forge and start DDT. There are several options. We’ll start a new job running the exercise code, so click on ‘Run’. You’ll see that a new window opens. Here we essentially provide all the information that we would put into a job script if we were doing a normal run.

For a simple job like this, we need to provide details in three sections of this new window: the application to run, resources, and job limits.

The application details are quite simple. You choose the executable to run, any arguments it may require, and the working directory in which you want the job to take place. For our job here, you can provide the path to gdb_exercise, leave the arguments blank, and choose the working directory to be the one containing gdb_exercise.

Let’s now choose what resources we want to use. If the ‘MPI’ box isn’t ticked, do so now. This will expand the MPI section. Make sure that ‘Slurm (generic)’ is listed as the implementation – if it isn’t, make sure to change that first.

We know that this code should work over two processes, so select:

- Number of processes = 2

- Number of nodes = 1

- Processes per node = 2

You can also add any other srun arguments you may want here. For us just now, we’ll leave it blank.

Finally, we need to say something about what a job script looks like. Make sure that ‘Submit to queue’ is ticked, then click on ‘Configure’. This will open a new window. We need to provide a submission template file. One is made available in the Forge installation directories, so enter /work/y07/shared/utils/core/arm/forge/22.1.3/templates/archer2.qtf. Then click on ‘OK’.

Submission template files

You can take a look at

/work/y07/shared/utils/core/arm/forge/22.1.3/templates/archer2.qtfto see what it contains. You’ll see it looks like a fairly standard ARCHER2 job script, with some parameters replaced with tags used by DDT to set the job parameters. If your job needs to launch differently, you can make your own copy of this script, edit it as necessary, and then tell DDT to use it.

You can set your job’s remaining parameters by clicking on the ‘Parameters’ button. Set the following for now:

- Wall clock limit = 00:10:00

- Partition =

standard - QoS =

short - Account =

ta000

So, the job can run for ten minutes at most on a standard partition node under the short QoS, and will be charged to the ta000 budget. This is just like a normal job script that you would submit to the queue with sbatch, and you can change these parameters to anything that would be accepted in a normal job.

No other sets of options should be enabled. At this point, everything should be ready to go. Click on Submit to start. If you are lucky, the job will get through the queue and start quickly.

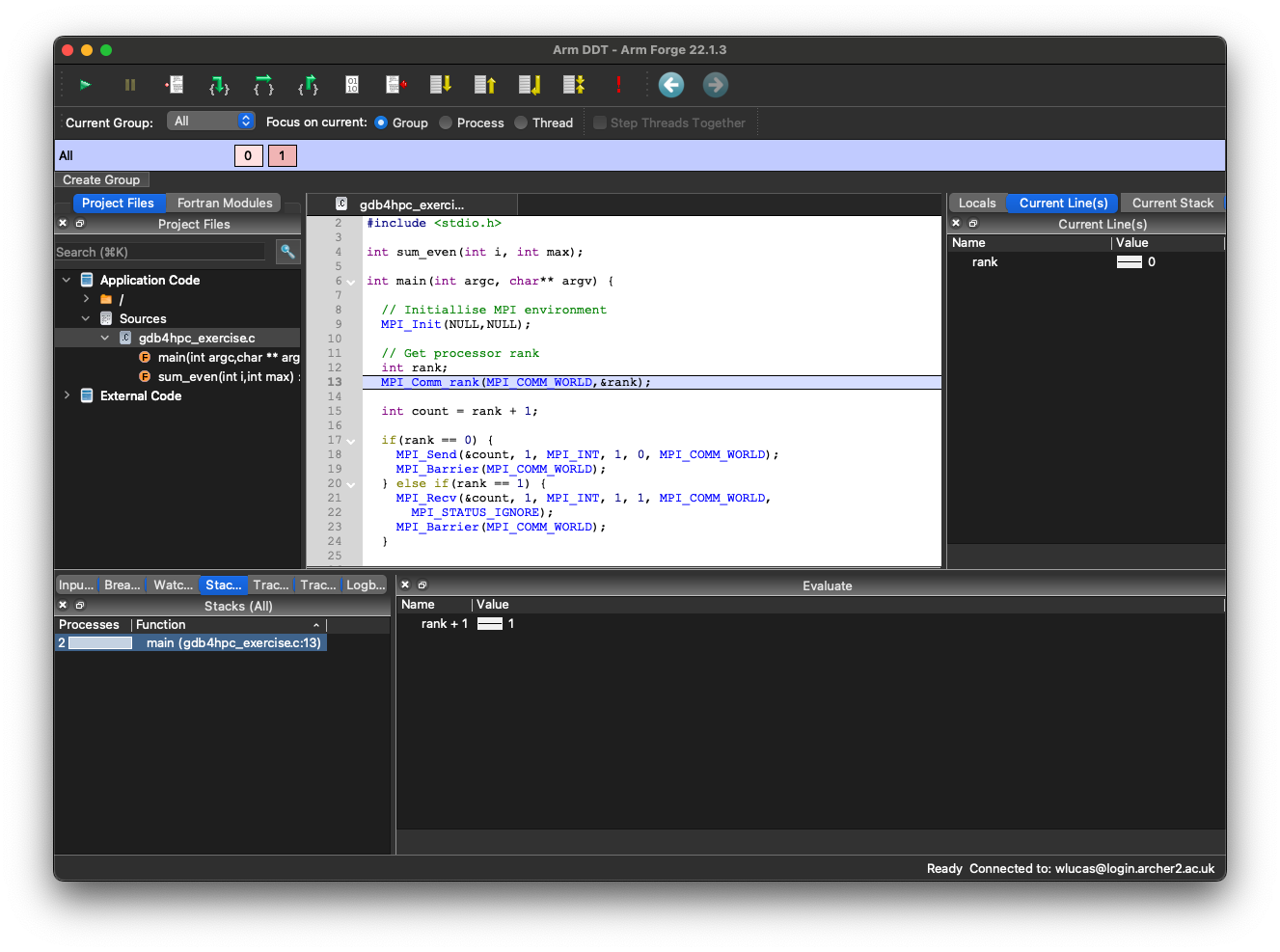

Once the job has started and the debugger connected, you’ll be faced with a window that contains at the centre the gdb4hpc_exercise.c source code. The program itself will execute and then halt early on at an initial breakpoint in main.

There’s a lot of information here:

- The central panel showing the source code has highlighted the lines that the execution has paused on. Both tasks have paused at line 13, so that line is highlighted.

- The panel to the left shows the source files and the functions within them. If you use Fortran modules, you can explore those here as well.

- The right hand panel allows you to view the values of variables and the stacks on each process. Note the little graphs next to the variables that show how they vary across processes.

- The bottom left panel has several tabs showing I/O, listing any breakpoints and watched variables you set, the full stack for each task, and tracepoints. The latter allow you to log variable values when the code moves through a certain line of source or a given function.

- The bottom right panel allows you to evaluate and watch statements given the current values of variables in the code. You can right click on an expression to compare it across processes or threads.

There are many powerful and quite easy to use tools here. Along the top are buttons to run the executable, pause, step in and step out. Click to the left of a line number in the source to set a breakpoint. Inspect and edit scalar variables or entire arrays, within or across processes, by right-clicking on them in the local variable panel. Separate processes into groups and execute them differently. You can also edit the source code directly from within DDT, then recompile and re-run. Thankfully, it will warn you if it realises that the source code has been edited more recently than the executable has been recompiled.

Exercise

Try to run the buggy version of

gdbhpc_exercisein DDT yourself using 2 processes. Can you see how you would have debugged it here?Solution

If you run without setting breakpoints, or if you continuously step over, you’ll see that the code eventually hangs at lines 19 and 21. The stack trace at the bottom left will show you that one process (process 0) is at line 19, and another one (process 1) is at line 21. Just as before, the code has deadlocked. The tags and receiving process number in the MPI calls must be fixed. If you carry on further, you’ll find that process 1 reaches

MPI_Finalize()but process 0 is stuck in thewhileloop in thesum_even()function. The stack trace should again help you. If you repeatedly run and pause, you’ll notice the value ofidoesn’t change in the top-right local variable viewer. No wonder the loop can never exit!

Profiling with MAP

Let’s now look at how to profile with MAP. As before, we’ll reuse the profiling experiment from earlier as we already have some experience. Make sure you have the arm/forge module loaded, re-download the .tar.gz containing the source code and extract it.

auser@ln01:~> module load arm/forge

auser@ln01:~> wget https://epcced.github.io/archer2-intro-develop/files/nbody-par.tar.gz

auser@ln01:~> tar -xzf nbody-par.tar.gz

For MAP to be able to profile the executable, we will need to link some extra libraries to it. The location of the libraries to link also depends on which compiler you are using. The link options for each compiler are:

- For the Cray compilers:

-L${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/cray/ofi -lmap-sampler-pmpi -lmap-sampler -Wl,--eh-frame-hdr -Wl,-rpath=${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/cray/ofi - For the GCC compilers:

-L${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/gnu/ofi -lmap-sampler-pmpi -lmap-sampler -Wl,--eh-frame-hdr -Wl,-rpath=${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/gnu/ofi - For the AOCC compilers:

-L${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/aocc/ofi -lmap-sampler-pmpi -lmap-sampler -Wl,--eh-frame-hdr -Wl,-rpath=${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/aocc/ofi

For MAP to extract line numbers from profiling information, we should also tell the compilers to add minimal debugging information – but not so much that it impacts performance. Linaro recommend the following for the Cray and GCC compilers:

- For the Cray C and C++ compilers:

-g1 -O3 -fno-inline-functions -fno-optimize-sibling-calls - For the Cray Fortran compiler:

-G2 -O3 -h ipa0 - For the GCC compilers:

-g1 -O3 -fno-inline -fno-optimize-sibling-calls

With CrayPat the compiler wrappers took care of adding all these options for us, but here we will need to do so manually. To do so, you can export them to the CFLAGS or FFLAGS environment variables, or if you prefer you can edit the Makefile and add them to those options there.

Assuming we are using the GCC compilers, let’s set the CFLAGS environment variable and then build the N-body programme with make.

Then, compile the code with make:

auser@ln01:~> export CFLAGS="-g1 -O3 -fno-inline -fno-optimize-sibling-calls -L${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/cray/ofi -lmap-sampler-pmpi -lmap-sampler -Wl,--eh-frame-hdr -Wl,-rpath=${FORGE_DIR}/map/libs/default/cray/ofi"

auser@ln01:~> make

You may receive warnings about unused arguments. You don’t need to worry about these – what matters is that MAP needs the libraries at runtime.

You can, if you like, launch profiling jobs much the way you did earlier for debugging jobs. At the same time, as profiling is often done ‘after the fact’, it is generally easier to run the jobs from a normal job script and then load the output into MAP for visualisation. You can convert any job script to run a MAP profiling job by making sure that the arm/forge module is loaded during the script and changing the srun command to a map command of the following form:

map -n <number of MPI processes> --mpi=slurm --mpiargs="--hint=nomultithread --distribution=block:block" --profile ./my_executable

You can then submit the job as normal with sbatch. Once completed, you should find a .map file in the job’s working directory with a name containing the executable name, the number of MPI tasks, OpenMP threads, and nodes, and the run time, for example nbody-parallel_64p_1n_1t_2023-11-30_11-57.map.

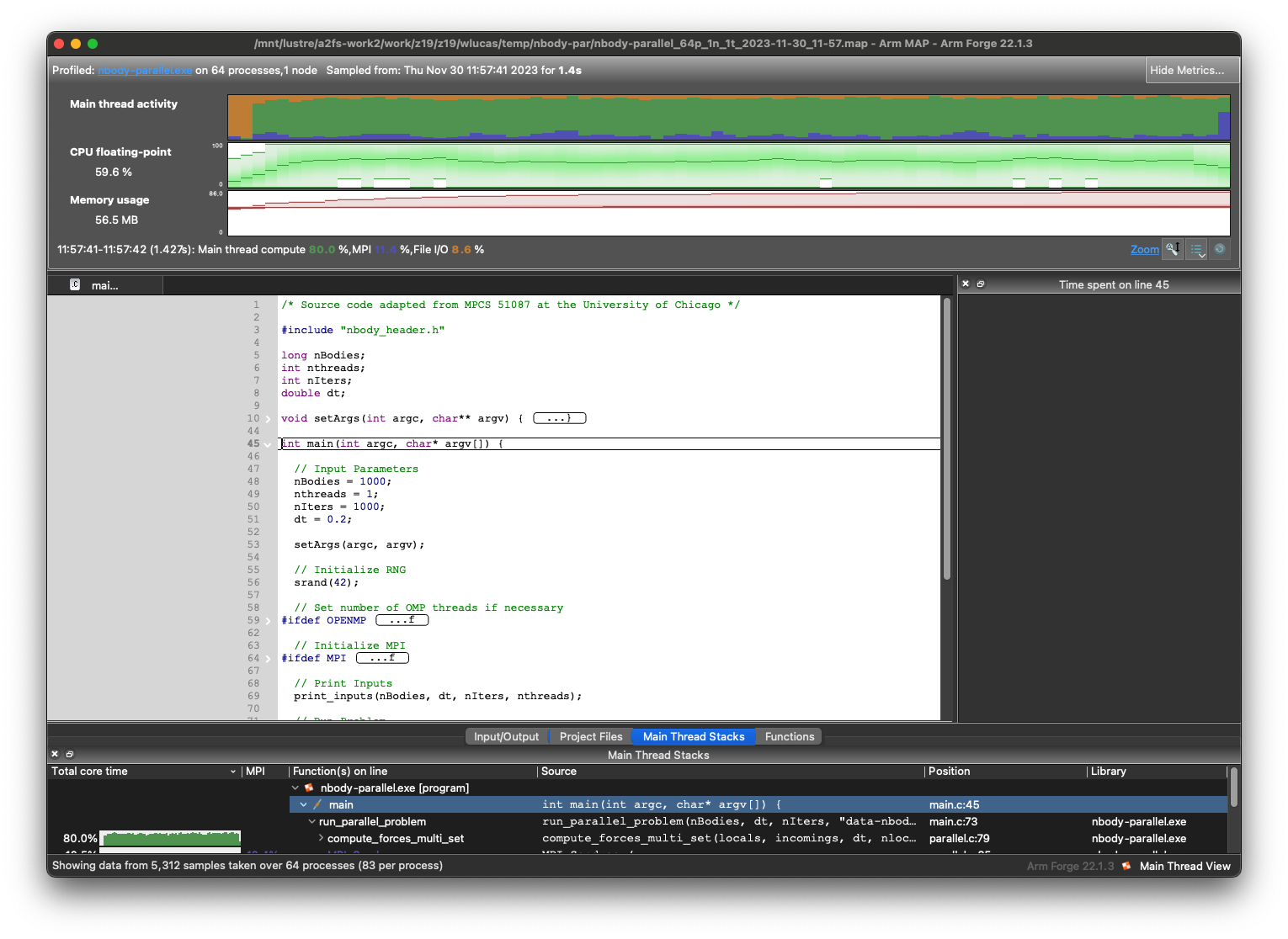

Any .map file can be opened with the Forge GUI. Once your client is connected to ARCHER2, click on ‘MAP’ and then ‘Load Profile Data File’. If the run was so short that not many samples were collected, you may be warned. Once open, you will be faced with a screen showing the timeline of execution, broken down into different sources of time spent, floating point activity and memory usage. You should also see the code and a window breaking down how time was spent on that line of code (if enough time was spent there for this to be detected). At the bottom are the call stacks and functions with total time spent on each as well as mini previews of their own profiles.

As with DDT, there is a lot of functionality here. You can click and drag across the main timelines at the top of the screen to zoom in; right-click to zoom back out. You can view different sets of timelines through the ‘Metrics’ menu at the top. These give more information on MPI call duration, bandwidth and call frequency, CPU instruction throughput and branching, and I/O read and write rates.

Exercise

Recompile

nbody-parallel.exefor use with MAP and then profile a run across 64 MPI processes. Try to determine which parts of the code are consuming the most time. Can see you see any points where MPI communications appear to be slowing the simulation down? A hint: you can increase the number of iterations via the-iparameter to get a longer runtime.Solution

There are a few things to take note of. First is that the first portion of the run will be spent doing I/O. Once running, the code does a good job of always doing something, rather than waiting on I/O or communication. If you look in the ‘Main Thread Stacks’ or ‘Functions’ tab at the bottom, you should see that most time is spent in the

compute_forces_multi_setfunction. You should be able to also see the specific lines within this function. Looking at the MPI activity, you may see step-shaped features, almost like a sawtooth wave. You can identify these as belonging toMPI_Sendrecvcalls which are blocking and so holding up the code.

More with Forge

This is as much of Forge as we will cover for now, but to learn more you can read the ARCHER2 documentation and the Linaro Forge documentation. In particular, you may find the ARCHER2 documentation on ‘offline’ debugging useful. This allows you to run post-mortem debugging for jobs which have crashed, which may be particularly useful if your job is large and needs to wait a long time in the queue.

Key Points

Linaro Forge provides powerful graphical tools for debugging and profiling.